Hawker Tempest

| Tempest | |

|---|---|

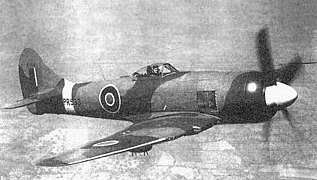

A Tempest V, NV696, during a test flight, November 1944 | |

| General information | |

| Type | Fighter aircraft |

| National origin | United Kingdom |

| Manufacturer | Hawker Aircraft |

| Primary users | Royal Air Force |

| Number built | 1,702[1] |

| History | |

| Introduction date | January 1944 |

| First flight | 2 September 1942 |

| Retired | 1953 |

| Developed from | Hawker Typhoon |

| Developed into | Hawker Sea Fury |

The Hawker Tempest is a British fighter aircraft that was primarily used by the Royal Air Force (RAF) in the Second World War. The Tempest, originally known as the Typhoon II, was an improved derivative of the Hawker Typhoon, intended to address the Typhoon's unexpected deterioration in performance at high altitude by replacing its wing with a thinner laminar flow design. Since it had diverged considerably from the Typhoon, it was renamed Tempest. The Tempest emerged as one of the most powerful fighters of World War II and at low altitude was the fastest single-engine propeller-driven aircraft of the war.[2]

Upon entering service in 1944, the Tempest performed low-level interception, particularly against the V-1 flying bomb threat, and ground attack supporting major invasions like Operation Market Garden. Later, it successfully targeted the rail infrastructure in Germany and Luftwaffe aircraft on the ground, as well as countering similar attacks by German fighters. The Tempest was effective in the low-level interception role, including against newly developed jet-propelled aircraft like the Messerschmitt Me 262.

The further-developed Tempest II did not enter service until after the end of hostilities. It had several improvements, including being tropicalised for combat against Japan in South-East Asia as part of the Commonwealth Tiger Force.

Design and development

[edit]Origins

[edit]During development of the earlier Hawker Typhoon, the design team, under the leadership of Sydney Camm, had already planned out a series of design improvements; these improvements culminated in the Hawker P. 1012, otherwise known as the Typhoon II or "Thin-Wing Typhoon".[3][4] Although the Typhoon was generally considered to be a good design, Camm and his design team were disappointed with the performance of its wing, which had proved to be too thick in its cross section, and thus created airflow problems which inhibited flight performance, especially at higher altitudes and speeds where it was affected by compressibility. The Typhoon's wing, which used a NACA 4 digit series wing section, had a maximum thickness-to-chord ratio of 19.5 per cent (root) to 12 per cent (tip),[5] in comparison to the Supermarine Spitfire's 13.2 per cent tapering to 6 per cent at the tip, the thinner design being deliberately chosen to reduce drag.[6][nb 1] In addition, there had been other issues experienced with the Typhoon, such as engine unreliability, insufficient structural integrity, and the inability to perform high altitude interception duties.[7]

In March 1940, engineers were assigned to investigate the new low–drag laminar flow wing developed by NACA in the United States, which was later used in the North American P-51 Mustang. A laminar flow wing adopted for the Tempest series had a maximum thickness-to-chord ratio of 14.5 per cent at the root, tapering to 10 per cent at the tip.[5][7] The maximum thickness of the Tempest wing was set further back at 37.5 per cent of the chord versus 30 per cent for the Typhoon's wing, reducing the thickness of the wing root by five inches on the new design.[5][7] The wingspan was originally greater than that of the Typhoon at 43 ft (13 m), but the wingtips were later "clipped" and the wing became shorter; 41 ft (12 m) versus 41 ft 7 in (12.67 m).[5]

The wing planform was changed to a near-elliptical shape to accommodate the 800 rounds of ammunition for the four 20 mm Hispano cannons, which were moved back further into the wing. The new wing had greater area than the Typhoon's,[nb 2] but the new wing design sacrificed the leading edge fuel tanks of the Typhoon. To make up for this loss in capacity, Hawker engineers added a new 21 in (53 cm) fuel bay in front of the cockpit, with a 76 Igal (345 L) fuel tank.[4][5] In addition, two inter-spar wing tanks, each of 28 Igal (127 L), were fitted on either side of the centre section and, starting with late model Tempest Vs, a 30 Igal (136 L) tank was carried in the leading edge of the port wingroot, giving the Tempest a total internal fuel capacity of 162 Igal (736 L).[8]

Another important feature of the new wing was Camm's proposal that the radiators for cooling the engine be fitted into the leading edge of the wing inboard of the undercarriage. This eliminated the distinctive "chin" radiator of the Typhoon and improved aerodynamics.[5][7] A further improvement of the Tempest wing over that of the Typhoon was the exceptional, flush-riveted surface finish, essential on a high-performance laminar flow airfoil.[9] The new wing and airfoil, and the use of a four-bladed propeller, acted to eliminate the high frequency vibrations that had plagued the Typhoon.[10] The design team also chose to use the new Mark IV version of the Napier Sabre H-block 24 cylinder engine for the Tempest, drawings of which had become available to Hawker in early 1941.[11]

In February 1941, Camm commenced a series of discussions with officials within the Ministry of Aircraft Production on the topic of the P.1012.[11] In March 1941 of that year, clearance to proceed with development of the design, referred to at this point as the Typhoon II, was granted. The design at the time encompassed the Sabre E.107C (as it was then known) with a four-blade propeller, 42 ft span elliptical wing with six cannon armament; while the front of the fuselage was redesigned the rear was unchanged from the Typhoon.[12] At this point, work was undertaken by a team of 45 draughtsmen at Hawker's wartime experimental design office at Claremont, Esher to convert the proposal into technical schematics from which to commence manufacture.[11] In March 1941, the Air Ministry issued specification F.10/41 that had been written to fit the aircraft. The performance estimate given to MAP was 455 mph at 26,000 ft.[12] In September Camm was told that the Air Ministry's Director of Technical Development that they had decided to have two Typhoons converted to the new design. By October 1941, development of the proposal had advanced to the point where the new design was finalised.[11]

Prototypes

[edit]

On 18 November 1941, a contract was issued by the Air Ministry for a pair of prototypes of the "Typhoon Mark II"; the new fighter was renamed "Tempest" on 28 February 1942.[5][11][nb 3][a] Complications were added to the Tempest program by external factors in the form of engine issues: the Rolls-Royce Vulture engine and corresponding Hawker Tornado aircraft which was being developed in parallel to the Typhoon were both terminated. This measure turned out to be prudent, as engine development was not trouble-free on some of the variants of the Tempest.[14] The Bristol Centaurus radial engine was now also considered for equipping the Typhoon and Camm was forewarned in October 1941 to expect a request for a Centaurus to be fitted. This was confirmed in February as an order for six prototypes with the Centaurus; the DTD stating that the development was highest priority.[15]

Delays with the Sabre IV development affected the project. With the expected first flight date for the Tempest was September 1942, the engine for HM595 was changed to a Sabre II complete with the Typhoon cooling system and under nose radiator.[12] Due to this previous experience on other programmes, the Air Ministry was sufficiently motivated to request that Tempest prototypes be built using different engines so that, if a delay hit one engine, an alternative powerplant would already be available.[11]An order was approved for six more prototypes with alternate engines in May and the contract for two with Sabres, two with Centaurus and two with Rolls Royce Griffons followed in June.[12]

The six prototypes built were as follows:[16][17]

- One Tempest Mk.I (serial number HM599), equipped with the Napier Sabre Mk.IV engine

- Two Tempest Mk.II (serial numbers LA602 and LA607), equipped with the Bristol Centaurus Mk.IV engine (LA607 later receiving a Centaurus Mk.V)[18]

- One Tempest Mk.III (serial number LA610), equipped with the Rolls-Royce Griffon 85 engine (originally planned for the Griffon IIB)[19]

- One Tempest Mk.IV (serial number LA614), which was never completed but planned to be equipped with a Griffon 61 engine

- One Tempest Mk.V (serial number HM595), equipped with the Napier Sabre Mk.II engine

The Tempest Mk.I featured other new features, such as a clean single-piece sliding canopy in place of the car-door framed canopy, and it used wing radiators instead of the "chin" radiator.[nb 4] Due to development difficulties with the Sabre IV engine and its wing radiators, the completion of the Mk.I prototype, HM599, was delayed, and thus it was the Mk.V prototype, HM595, that would fly first.[20]

On 2 September 1942, the Tempest Mk.V prototype, HM595, conducted its maiden flight, flown by Philip Lucas from Langley, Berkshire, England.[20] HM595, which was powered by a Sabre II engine, retained the Typhoon's framed canopy and car-style door, and was fitted with the "chin" radiator, similar to that of the Typhoon.[16] It was quickly fitted with the same bubble canopy fitted to Typhoons, and a modified fin that almost doubled the vertical tail surface area, made necessary because the directional stability with the original Typhoon fin had been reduced over that of the Typhoon by the longer nose incurred by the new fuel tank. The horizontal tailplanes and elevators were also increased in span and chord; these were also fitted to late production Typhoons.[16][21] Test pilots found the Tempest a great improvement over the Typhoon in performance; in February 1943 the pilots from the Aeroplane & Armament Experimental Establishment at Boscombe Down reported that they were impressed by "a manoeuvrable and pleasant aircraft to fly with no major handling faults".[10]

On 24 February 1943, the second prototype HM599 first flew, representing the "Tempest Mk.I" equipped with the Napier Sabre IV engine; this flight had been principally delayed by protracted problems and slippages encountered in the development of the new Sabre IV engine.[10] Construction had been on hold (so parts could be used for possible repairs to the first prototype) until HM595 was converted to Sabre II.[12] HM599 was at first equipped with the older Typhoon cockpit structure and vertical tailplane. The elimination of the "chin" radiator did much to improve overall performance, leading to the Tempest Mk.I quickly becoming the fastest aircraft that Hawker had built at that time, having attained a speed of 466 mph (750 km/h) during test flights.[22] The Sabre IV was failing testing and so the Mk I Tempest was abandoned by the MAP.[23]

On 27 November 1944, the Tempest Mk.III prototype, LA610, conducted its first flight; it was decided to discontinue development work on the Mk.III, this was due to priority for the Griffon engine having been assigned to the Supermarine Spitfire instead.[14][nb 5] The Air Ministry had seen the Mk III as a replacement for the Hurricane in ground attack, with the narrower engine giving a better view as well but the Typhoon would be the interim aircraft for the role. In practice the Typhoon proved very good for ground attack.[24]

Work on the Tempest Mk.IV variant was abandoned without any prototype being flown at all.[14] The Tempest Mk.II, which was subject to repeated delays due to its Centaurus powerplant, was persisted with, but would not reach production in time to see service during the Second World War.[21] Continual problems with the Sabre IV meant that only the single Tempest Mk.I (HM599) was built; consequently, Hawker proceeded to take the Sabre II-equipped "Tempest V" into production instead.[25]

In August 1942, even before the first flight of the prototype Tempest V had been conducted, a production order for 400 Tempests was placed by the Air Ministry.[20][b] This order was split, with the initial batch of 100 being Tempest V "Series I"s, powered by the 2,235 hp (1,667 kW) Sabre IIA series engine, which had the distinctive chin radiator, while the rest were to have been produced as the Tempest I, equipped with the Sabre IV and leading-edge radiators. These 300 Tempest Is were intended to replace an order for a similar quantity of Typhoons placed with the Gloster Aircraft Company.[20][nb 6] As it transpired, the difficulties with the Sabre IV and the wing radiators led to this version never reaching production, the corresponding order was switched to 300 Tempest V "Series 2"s instead.[20][27][nb 7]

Tempest Mk.V

[edit]

During early 1943, a production line for the Tempest Mk.V was established in Hawker's Langley facility, alongside the existing manufacturing line for the Hawker Hurricane.[21] Production was initially slow, claimed to be due to issues encountered with the rear spar. On 21 June 1943, the first production Tempest V, JN729, rolled off the production line[21][25] and its maiden flight was conducted by test pilot Bill Humble.[29]

During production of the first batch of 100 Tempest V "Series Is", distinguishable by their serial number prefix JN, several improvements were progressively introduced and were used from the outset on all succeeding Tempest V "Series 2s", with serial number prefixes EJ, NV and SN. The fuselage/empennage joint originally featured 20 external reinforcing "fishplates", similar to those fitted to the Typhoon, but it was not long before the rear fuselage was strengthened and, with the fishplates no longer being needed, the rear fuselage became detachable.[30] The first series of Tempest Vs used a built-up rear spar pick-up/bulkhead assembly (just behind the cockpit) which was adapted from the Typhoon. Small blisters on the upper rear wing root fairing covered the securing bolts. This was later changed to a new forged, lightweight assembly which connected to new spar booms: the upper wing root blisters were replaced by small "teardrop" fairings under the wings.[30]

The first 100 Tempest Vs were fitted with 20 mm (0.79 in) Hispano Mk.II cannon with long barrels which projected ahead of the wing leading edges and were covered by short fairings; later production Tempest Vs switched to the short-barrelled Hispano Mk.Vs, with muzzles flush with the leading edges.[27] Early Tempest Vs used Typhoon-style 34 by 11 in (86 by 28 cm) five-spoke wheels, but most had smaller 30 by 9 in (76 by 23 cm) four-spoke wheels.[31] The new spar structure of the Tempest V also allowed up to 2,000 lb (910 kg) of external stores to be carried underneath the wings.[25] As a result, several early production Tempest V aircraft underwent extensive service trials at Boscombe Down for clearance to be fitted with external stores, such as one 250–1,000 lb (110–450 kg) bomb or eight "60lb" air-to-ground RP-3 rockets under each wing. On 8 April 1944, the Tempest Mk.V attained general clearance[32] to carry such ordnance, but few Tempest Mk.V deployed bombs operationally during the war.[21][33] Rockets were never used operationally during the war by the Mk.Vs.[34]

As in all mass-produced aircraft, there may have been some overlap of these features as new components became available. In mid-to-late 1944 other features were introduced to both the Typhoon and Tempest: A Rebecca transponder unit was fitted, with the associated aerial appearing under the portside centre section. A small, elongated oval static port appeared on the rear starboard fuselage, just above the red centre spot of the RAF roundel. This was apparently used to measure the aircraft's altitude more accurately.[citation needed]

Unusually, in spite of the Tempest V being the RAF's best low- to medium-altitude fighter, it was not equipped with the new Mk.IIC gyroscopic gunsight (as fitted in RAF Spitfires and Mustangs from mid-1944), which would have considerably improved the chances of shooting down opposing aircraft. Tempest pilots continued to use either the Type I Mk.III reflector gunsight, which projected the sighting graticule directly onto the windscreen, or the Mk.IIL until just after the Second World War, when the gyro gunsight was introduced in Tempest IIs.[35]

Two Tempest Vs, EJ518 and NV768, were fitted with Napier Sabre Vs and experimented with several different Napier-made annular radiators, with which they resembled Tempest IIs. This configuration proved to generate less drag than the standard "chin" radiator, contributing to an improvement in the maximum speed of some 11 to 14 mph.[36] NV768 was later fitted with a ducted spinner, similar to that fitted to the Fw 190 V1.[22][37]

47 mm anti tank gun trials

[edit]

Tempest V SN354 was fitted with two experimental underwing Class P 47 mm guns (built by Vickers) just after the war.[38][39][c] These guns were part of a project started in mid-1942 to develop a more powerful airborne anti-tank gun than the Vickers 40 mm Class S gun which had been used on the Hurricane IID.[38][d] The Vickers guns were housed in long slim streamlined gun pods carried on the bomb racks[34] and had 38 rounds each.[41] Surviving photographs suggests that the 20 mm wing guns were removed for this installation. Testing of the guns revealed that the weapon had potential, but no production was undertaken.[34]

Tempest Mk.II

[edit]

As a result of the termination of the Tornado project, Sydney Camm and his design team transferred the alternative engine proposals for the Tornado to the more advanced Tempest.[17] Thus, it was designed from the outset to use the Bristol Centaurus 18 cylinder radial engine as an alternative to the liquid cooled engines which were also proposed. A pair of Centaurus-powered Tempest II prototypes were completed.[42] Apart from the new engine and cowling, the Tempest II prototypes were similar to early series Tempest Vs. The Centaurus engine was closely cowled and the exhaust stacks grouped behind and to either side of the engine: to the rear were air outlets with automatic sliding "gills". The carburettor air intakes were in the inner leading edges of both wings, an oil cooler and air intake were present in the inner starboard wing. The engine installation owed much to examinations of a captured Focke-Wulf Fw 190, and was clean and effective.

On 28 June 1943, the first Tempest II, LA602, flew powered by a Centaurus IV (2,520 hp/1,879 kW) driving a four-blade propeller. LA602 initially flew with a Typhoon-type fin and rudder unit. This was followed by the second, LA607, which was completed with the enlarged dorsal fin and first flew on 18 September 1943: LA607 was assigned to engine development.[43][nb 8] The first major problem experienced during the first few flights was serious engine vibrations, which were cured by replacing the rigid, eight-point engine mountings with six-point rubber-packed shock mounts. In a further attempt to alleviate engine vibration, the four-blade propeller was replaced with a five-blade unit; eventually, a finely balanced four bladed unit was settled on.[44][45] Problems were also experienced with engine overheating, poor crankshaft lubrication, exhaust malfunctions and reduction-gear seizures. Because of these problems, and because of the decision to "tropicalise" all Tempest IIs for service in the South-East Asian theatre, production was delayed.[43][46]

Orders had been placed as early as September 1942 for 500 Tempest IIs to be built by Gloster but in 1943, because of priority being given to the Typhoon, a production contract of 330 Tempest IIs was allocated instead to Bristol, while Hawker were to build 1,800. This switch delayed production even more.[46][47] On 4 October 1944, the first Tempest II was rolled off the line; the first six production aircraft soon joined the two prototypes for extensive trials and tests.[46] With the end of the Second World War in sight, orders for the Tempest II were trimmed or cancelled; after 50 Tempest IIs had been built by the Bristol shadow factory near Banwell, production was stopped and shifted back to Hawker, which built a total of 402, in two production batches: 100 were built as fighters, and 302 were built as fighter-bombers (FB II) with reinforced wings and wing racks capable of carrying bombs of up to 1,000 lb.[48]

Physically, the Tempest II was longer than the Tempest Mk.V (34 ft 5 in (10.49 m) versus 33 ft 8 in (10.26 m) and 3 in (76 mm) lower. The weight of the heavier Centaurus engine (2,695 pounds (1,222 kg) versus 2,360 pounds (1,070 kg) was offset by the absence of a heavy radiator unit, so that the Tempest II was only some 20 pounds (9.1 kg) heavier overall. Performance was improved; maximum speed was 442 mph (711 km/h) at 15,200 ft (4,600 m) and climb rate to the same altitude took four and a half minutes compared with five minutes for the Tempest Mk.V; the service ceiling was also increased to 37,500 ft (11,400 m).[49]

Tropicalising measures included the installation of an air filter and intake in the upper forward fuselage, just behind the engine cowling, and the replacement of the L-shaped pitot head under the outer port wing by a straight rod projecting from the port outer wing leading edge. All production aircraft were powered by a (2,590 hp (1,930 kW) Centaurus V driving a 12 ft 9 in (3.89 m) diameter Rotol propeller.[31] Tempest IIs produced during the war were intended for combat against Japan and would have formed part of Tiger Force, a proposed British and Commonwealth long-range bomber force based on Okinawa to attack the Japanese home islands.[50] The Pacific War ended before they could be deployed.[45]

Tempest Mk.VI

[edit]

Various engineering refinements that had gone into the Tempest II were incorporated into the last Tempest variant, designated as the Tempest VI. This variant was furnished with a Napier Sabre V engine with 2,340 hp (1,740 kW). The more powerful Sabre V required a bigger radiator which displaced the oil cooler and carburettor air intake from the radiator's centre; air for the carburettor was drawn through intakes on the leading edge of the inner wings, while the oil cooler was located behind the radiator. Most Tempest VIs were tropicalised, the main feature of this process being an air filter which was fitted in a fairing on the lower centre section.[45] Other changes included the strengthening of the rear spar and the inclusion of spring tabs, which granted the variant superior handling performance.[45]

The original Tempest V prototype, HM595, was extensively modified to serve as the Tempest VI prototype.[45] On 9 May 1944, HM595 made its first flight after its rebuild, flown by Bill Humble. In December 1944, HM595 was dispatched to Khartoum, Sudan to conduct a series of tropical trials. During 1945, two more Tempest V aircraft, EJ841 and JN750, were converted to the Tempest VI standard in order to participate in service trials at RAF Boscombe Down.[45]

At one point, 250 Tempest VIs were on order for the RAF; however, the end of the war led to many aircraft programs being cut back intensively, leading to only 142 aircraft being completed.[45] For a long time, it was thought there were Tempest VIs that had been converted for target towing purposes; however, none of the service histories of the aircraft show such conversions and no supporting photographic evidence has been found. The Tempest VI was the last piston-engined fighter in operational service with the RAF, having been superseded by jet propelled aircraft.

Drawing board designs

[edit]In 1943, Camm initiated work on a new design for fighter equipped with the at that point unbuilt Rolls-Royce R.46 engine. The project designated as the P.1027 was essentially a slightly enlarged Tempest with the R.46 engine, which Hawker expected to develop around 4,000 hp (2,980 kW). This engine would have driven a pair of four-bladed contra-rotating propellers. The radiator was relocated into a ventral bath set underneath the rear fuselage and wing centre section: the wingspan was 41 ft (12 m) and the length was 37 ft 3 in (11.35 m).[51]

However, work upon the P.1027 design was soon dropped in favour of concentrating upon a further developed design, the P.1030, in September It featured wing leading edge radiators and had larger overall dimensions of 42 ft (13 m) wingspan and 39 ft 9 in (12.12 m) length. The top speed was calculated as 509 mph (819 km/h) at 20,000 ft, with a rate of climb of 6,400 ft/min (1,951 m/min). Service ceiling was projected to be more than 42,000 ft (13,000 m).[51] Work on both was ultimately dropped when Camm decided to focus design efforts upon the more promising jet engine designs he was working on instead.

Design

[edit]This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (September 2016) |

The Tempest was a single engine fighter aircraft that excelled at low-level flight. In service, its primary role soon developed into performing "armed reconnaissance" operations, often deep behind enemy lines. The Tempest was particularly well suited to the role because of its high speed at low to medium altitudes, its long range when equipped with two 45-gallon drop tanks, the good firepower of the four 20mm cannon and the good pilot visibility.[52] The three-piece windscreen and side windows of the Tempest had directly benefited from examination of captured Focke-Wulf Fw 190s, improvements included the careful design and positioning of the frame structure, blind spots being reduced to an absolute minimum. It had a bullet-resistant centre panel made up of two layers, the outer 1.5 in (38 mm) thick and the inner 0.25 in (6.4 mm).[53]

The majority of production Tempests were powered by a single high-powered Napier Sabre II 24-cylinder engine. All versions of the Sabre drove either a four-bladed, 14 ft (4.3 m) diameter de Havilland Hydromatic or Rotol propeller. Starting with EJxxx series, on the Tempest V, both the improved Sabre IIB and IIC were used, these engines were capable of producing over 2,400 hp (1,800 kW) on emergency boost for short periods of time.[54][55] Alternative engines were used on some production variants, such as the Tempest II, for which a single Bristol Centaurus 18 cylinder radial engine was adopted, or the final Tempest VI, upon which a Napier Sabre V was used. Early on in development, the adoption of several other engines was proposed, some of which were tested upon multiple prototypes.[14]

The wing of the Tempest was one of its more significant design features, having been developed from the Typhoon to use a thinner laminar flow design approach. The wing planform was of a near-elliptical shape; the aircraft's armament of four 20 mm Hispano cannons with 800 rounds of ammunition was also embedded into the wing.[5] The ailerons were fitted with spring-loaded tabs which lightened the aerodynamic loads, making them easier for the pilot to use and dramatically improving the roll rate above 250 mph (400 km/h).[25][32] The spar structure of the Tempest V also allowed the wings to carry up to 2,000 pounds (910 kg) of external stores. Also developed specifically for the Tempest by Hawker was a streamlined 45 gal (205 L) "drop tank" to extend the operational radius by 500 mi (800 km) and carrier fairing; the redesigned wing incorporated the plumbing for these tanks, one to each wing.[25][49]

The main undercarriage was redesigned from the Typhoon, featuring lengthened legs and a wider track (16 ft; 4.9 m) to improve stability at the high landing speed of 110 mph (180 km/h), and to allow tip clearance for a new de Havilland 14 ft (4.3 m) diameter four-blade propeller. The main undercarriage units were Dowty levered suspension units incorporating trunnions which shortened the legs as they retracted.[54][56] The retractable tailwheel was fully enclosed by small doors and could be fitted with either a plain Dunlop manufactured tyre, or a Dunlop-Marstrand "twin-contact" anti-shimmy tyre.[54]

During development, Camm and the Hawker design team had placed a high priority on making the Tempest easily accessible to both air and ground crews; to this end, the forward fuselage and cockpit areas of the earlier Hurricane and the Tempest and Typhoon families were covered by large removable panels providing access to as many components as possible, including flight controls and engine accessories. Both upper wing roots incorporated panels of non-slip coating. For the pilot a retractable foot stirrup under the starboard root trailing edge was linked to a pair of handholds which were covered by spring-loaded flaps. Through a system of linkages, when the canopy was open the stirrup was lowered and the flaps opened, providing easy access to the cockpit; as the canopy was closed, the stirrup was raised into the fuselage and the flaps snapped shut.

Operational history

[edit]

By April 1944, the Tempest V had attained general acceptance and was in the hands of operational squadrons; 3 Squadron was the first to be fully equipped, closely followed by 486 (NZ) Squadron (the only Article XV squadron to be equipped with the Tempest during the Second World War), replacing their previous Typhoons.[32] A third unit—56 Squadron—initially kept its Typhoons and was then temporarily equipped with Spitfire IXs until sufficient supplies of Tempests were available.[57][nb 9] By the end of April 1944, these units were based at RAF Newchurch in Kent a new "Advanced Landing Ground" (ALG), where they formed 150 Wing, commanded by Wing Commander Roland Beamont. The new Wing was part of the Second Tactical Air Force (2nd TAF).

Most of the operations carried out by 150 Wing comprised high-altitude fighter sweeps, offensive operations known as "Rangers", as well as reconnaissance missions. Prior to the Normandy landings, Tempests would routinely conduct long-range sorties inside enemy territory and penetrate into Northern France and the Low Countries, using a combination of cannons and bombs to attack airfields, radar installations, ground vehicles, coastal shipping and the launch sites for the German V-1 flying bombs.[32] The build-up of Tempest-equipped squadrons was increased rapidly, in part due to factors such as the V-1 threat, although a labour strike in Hawker's assembly shop adversely affected this rate; by September 1944, five frontline Tempest squadrons with a total of 114 aircraft were in operation.[32]

In June 1944, the first of the V-1s were launched against London; the excellent low-altitude performance of the Tempest made it one of the preferred tools for handling the small fast-flying unmanned missiles. 150 Wing was transferred back to the RAF Fighter Command; the Tempest squadrons soon racked up a considerable percentage of the total RAF kills of the flying bombs (638 of a total of 1,846 destroyed by aircraft).[32][58][page needed] Using external drop tanks, the Tempest was able to maintain standing patrols of four and half hours off the south coast of England in the approach paths of the V-1s.[59] Guided by close instructions from coastal radar installation, Tempests would be positioned ready for a typical pursuit and would either use cannon fire or nudge the V-1 with the aircraft itself to destroy it.[60]

In September 1944, Tempest units, based at forward airfields in England, supported Operation Market Garden, the airborne attempt to seize a bridgehead over the Rhine. On 21 September 1944, as the V-1 threat had receded, the Tempest squadrons were redeployed to the 2nd TAF, effectively trading places with the Mustang III squadrons of 122 Wing, which became part of the Fighter Command units deployed on bomber escort duties.[61] 122 Wing now consisted of 3 Sqn., 56 Sqn., 80 Sqn., 274 Sqn. (to March 1945), and 486(NZ)Sqn. From 1 October 1944 122 Wing was based at ALG B.80 (Volkel) near Uden, in the Netherlands.[61] During the early phase of operations, the Tempest regularly emerged victorious and proved to be a difficult opponent for the Luftwaffe's Messerschmitt Bf 109G and Fw 190 fighters to counter.[32]

Armed reconnaissance missions were usually flown by two sections (eight aircraft), flying in finger-four formations, which would cross the front lines at altitudes of 7,000 to 8,000 feet: once the Tempests reached their allocated target area the lead section dropped to 4,000 ft (1,200 m) or lower to search for targets to strafe, while the other section flew cover 1,000 ft (300 m) higher and down sun. After the first section had carried out several attacks, it swapped places with the second section and the attacks continued until all ammunition had been exhausted, after which the Tempests would return to base at 8,000 ft.[62] As many of the more profitable targets were usually some 250 miles from base, the Tempests typically carried two 45-gallon drop tanks which were turned on soon after takeoff. Although there were fears that the empty tanks would explode if hit by flak, the threat never eventuated and, due to the tanks being often difficult to jettison, they were routinely carried throughout an operation with little effect on performance, reducing maximum speed by 5 to 10 mph and range by 2 per cent.[62][63]

Between October and December 1944, the Tempest was practically withdrawn from combat operations for overhaul work, as well as to allow operational pilots to train newcomers.[60] The overhaul process involved the replacement or major servicing of their engines and the withdrawal of the limited number of aircraft which were equipped with spring-tabs; these increased manoeuvrability so much that there was a risk of damaging the airframe. In December 1944, upon the Tempest's reentry into service, the type had the twin tasks of the systematic destruction of the North German rail network along with all related targets of opportunity, and the maintenance of air supremacy within the North German theatre, searching for and destroying any high-performance fighter or bomber aircraft of the Luftwaffe, whether in the air or on the ground.[64]

In December 1944, a total of 52 German fighters were downed, 89 trains and countless military vehicles were destroyed, for the loss of 20 Tempests. Following the Luftwaffe's Unternehmen Bodenplatte of 1 January 1945, 122 Wing bore the brunt of low- to medium-altitude fighter operations for the Second Tactical Air Force, which had fortuitously evaded the extensive Bodenplatte raid, and had contributed to efforts to intercept the raiders.[43][65] During this time, Spitfire XIVs of 125 and 126 Wings often provided medium- to high-altitude cover for the Tempests, which came under intense pressure, the wing losing 47 pilots in January. In February 1945, 33 and 222 Sqns. of 135 Wing converted from Spitfire Mk IXs and, in March, were joined by 274 Sqn. 135 Wing was based at ALG B.77 (Gilze-Rijen airfield) in the Netherlands.[43][65] The intensity of operations persisted throughout the remainder of the war.[43]

Against advanced German planes

[edit]Piloting a Tempest on 19 April 1945, Flying Officer Geoffrey Walkington was the first to shoot down a Heinkel He 162, the Luftwaffe's then-latest jet fighter, which had just entered service with the I./JG 1 (1st Group of Jagdgeschwader 1 Oesau — "1st Fighter Wing Oesau").[66]

Tempest pilots, including French ace Pierre Clostermann, made the first Allied combat encounter with a Dornier 335 in April 1945. In his book The Big Show, he describes leading a flight of Hawker Tempests from No. 3 Squadron RAF over northern Germany, when they saw a lone unusual looking aircraft flying at maximum speed at treetop level. Detecting the British aircraft, the German pilot reversed course to evade. Despite the Tempests' considerable low altitude speed, Clostermann decided not to attempt to follow as it was obviously much quicker though one of the other two Tempests did pursue it briefly.[67]

During 1945, Tempests scored of a number of kills against the new German jets, including the Messerschmitt Me 262. Hubert Lange, a Me 262 pilot, said: "the Messerschmitt Me 262's most dangerous opponent was the British Hawker Tempest — extremely fast at low altitudes, highly manoeuvrable and heavily armed."[68]

Some Me 262s were destroyed using a tactic known to 135 Wing as the "Rat Scramble";[69] Tempests on immediate alert took off when an Me 262 was reported to be airborne. They did not directly intercept the jet, but instead flew towards the airbase at Rheine-Hopsten, known to base Me 262s and Ar 234s.[70] The aim was to attack jets on their landing approach, when they were at their most vulnerable, travelling slowly, with flaps down and incapable of rapid acceleration. The Germans responded by creating a "flak lane" of over 150 of the Flakvierling quadruple 20 mm AA batteries at Rheine-Hopsten, to protect the approaches.[71][nb 10] After seven Tempests were lost to anti-aircraft fire at Rheine-Hopsten in a single week, the "Rat Scramble" was discontinued. For a few days in March 1945, a strict "No, repeat, No ground attacks" policy was imposed.[72]

Air combat success ratio

[edit]In air-to-air combat, the Tempest units achieved an estimated air combat success ratio of about 8:1, scoring 239 confirmed victories (not including the additional "victories" against the unmanned V-1 flying bomb), 9 probable victories, and 31 losses and probable losses.[73][74]

The top-scoring Tempest pilot was Squadron Leader David Fairbanks DFC, an American who joined the Royal Canadian Air Force in 1941. By mid-1944, he was flying with 274 Squadron. When he was shot down and made a prisoner of war in February 1945, he had destroyed 11 or 12 German aircraft (and one shared), to make him the highest-scoring Tempest ace.[75]

Other activities

[edit]

Early flights by RAF pilots found the Tempest, unlike the Typhoon, was buffet-free up to and somewhat beyond 500 mph (800 km/h).[32] During 1944, several veteran USAAF pilots flew the Tempest in mock combat exercises held over the south of England; the consensus from these operations was that it was roughly akin to the American Republic P-47 Thunderbolt. According to aviation author Francis K. Mason, the Tempest was commonly accepted as the best–performing RAF fighter in operational service by VE Day.[32] Following the end of the war, the RAF decided upon the Tempest as its standard fighter, pending the introduction of newer aircraft, many of which would be developed post-war, such as the de Havilland Hornet and the de Havilland Vampire, as well as the Gloster Meteor. A number of squadrons would operate the Tempest as their final piston-engined type before converting to the new generation of jet-powered fighter aircraft that would come to dominate the next decade and beyond.[43]

Far East

[edit]The later Tempest Mk.II was tropicalised as it had been decided that this variant would be intended for combat against Japan. The envisioned role for the type would have been as a purpose-built type which would participate in the Tiger Force, which was a proposed British Commonwealth long-range bomber force to have been stationed on Okinawa as a forward base for operations against the Japanese mainland.[50] Before the Tempest Mk.II entered operational service, the Pacific War ended.[45] By October 1945, a total of 320 Tempest IIs had been delivered to maintenance units stationed at RAF Aston Down and RAF Kemble; these aircraft were mainly dispatched to squadrons stationed overseas in Germany and in India, along with other locations such as Hong Kong and Malaysia.[45] On 8 June 1946, a Tempest II, flown by Roland Beamont, led the flypast at the London Victory Celebrations of 1946. RAF Tempest IIs saw combat use against guerrillas of the Malayan National Liberation Army during the early stages of the Malayan Emergency.[45]

Post war

[edit]A total of 142 Tempest Mk VI were produced, which equipped nine squadrons of the RAF, five of these being stationed in the Middle East due to its suitability for such environments. This particular variant was anticipated to have a short lifetime and their phasing out commenced in 1949. During the 1950s, the Tempest was mainly used in its final capacity as a target tug aircraft. In 1947, the RAF transferred a total of 89 Tempest FB IIs to the Indian Air Force (IAF), while another 24 were passed on to the Pakistani Air Force (PAF) in 1948. Both India and Pakistan would operate the Tempest until 1953.[45] Several of these aircraft remain in existence, with three being restored to airworthiness in the United States and New Zealand. The restoration of an IAF Tempest Mk.II, MW376, in New Zealand was stalled due to the unexpected death of the owner in 2013, the aircraft being sold to a Canadian enthusiast; as of April 2016, MW376 was receiving extensive work at facilities in Kelowna, British Columbia, Canada. It is being restored to an operational condition.

Variants

[edit]- Tempest Mk. I

- Prototype fitted with the Napier Sabre Mk. IV inline piston engine with oil coolers and radiators placed in the wing to reduce drag, one aircraft built.

- Tempest Mk. II

- Single-seat fighter aircraft for the RAF, fitted with the Bristol Centaurus Mk. V engine, the short-barrelled Hispano Mk. V cannons and the standard Mk. V tail-unit.[18] The guns on the Tempest Mk. II had fewer cartridges compared to the Tempest Mk. V and Mk. VI (162 inboard and 152 outboard).[34] 402 built by Hawker at Langley and 50 by Bristol Aeroplane Company, Banwell.

- Tempest F. Mk. II – (F.2[e]) – Initial fighter version of the Tempest Mk. II. 100 built by Hawker[48] and 50 by Bristol.[18] Later upgraded to FB standard.[18]

- Tempest F.B. Mk. II – (FB.2) – Later fighter-bomber version of the Tempest Mk. II with strengthened wings and underwing hardpoints for bomb and rocket pylons, among other smaller changes.[18] 302 built by Hawker.[48][18]

- Tempest Mk. III

- Singe-seat experimental version of the Tempest, fitted with a Rolls-Royce Griffon 85 piston engine and contra-rotating propellers.[76] One prototype (LA610) built.[76]

- Tempest Mk. IV

- Tempest variant with a Rolls-Royce Griffon 61 piston engine.[76] One prototype (LA614) cancelled in February 1943.[76]

- Tempest Mk. V – F. Mk. V – (F.5)

- Single-seat fighter aircraft for the RAF, fitted with the Napier Sabre Mk. IIA, IIB or IIC, 801 built at Langley.[77]

- Tempest F. Mk. V Series 1 – Initial production version of the Tempest Mk V. Series 1 aircraft were fitted with four long-barrel 20 mm (.79 in) Hispano Mk. II cannons[nb 11] and continued to use some Typhoon components. 100 built.[77]

- Tempest F. Mk. V Series 2 – Later production version of the Tempest Mk. V, starting from Series 2. From Series 2 aircraft were fitted with four short-barrel 20 mm Mark V Hispano cannons and other production line changes. 701 built.[77]

- Tempest Mk. V "(PV)" – Experimental anti-tank version of the Tempest Mk. V fitted with two underwing experimental 47 mm PV (Class P, Vickers) anti-tank gunpods.[38] One Tempest Mk. V (SN354) modified for testing.[34]

- Tempest T.T. Mk. 5 – (TT.5) – After the Second World War a number of Tempest Mk Vs were converted to serve as target tugs.

- Tempest Mk. VI – F. Mk. VI (F.6)

- Single-seat fighter aircraft for the RAF, fitted with the Napier Sabre Mk. V engine (2,340 hp) but otherwise equivalent to the later Tempest Mk. V. 142 built.[78]

-

Tempest Mk. I – Prototype HM599

-

Tempest Mk. II – Early F.B. Mk. II production model PR533. Note the underwing bomb racks.

-

Tempest Mk. III – Prototype LA610

-

Tempest Mk. V – Early production model, note the protruding barrels of the 20 mm Hispano Mk.II guns.

-

Tempest Mk. VI – Early production model NX201.

Operators

[edit] Canada (One Tempest V, acquired postwar for trials.[79])

Canada (One Tempest V, acquired postwar for trials.[79]) India

India New Zealand

New Zealand Pakistan

Pakistan United Kingdom

United Kingdom

Surviving aircraft

[edit]

Airworthy

[edit]- Mk.II G-TEMT/MW763 - First built as Tempest II and taken on charge with RAF with serial 'MW763' in 1945. In 1948, the aircraft transferred to the IAF with serial 'HA586'. In 1989, it was transferred to Brooklands in Surrey with Autokraft Ltd with new civil registration G-TEMT, In 1997, it kept its civilian registration of G-TEMT and moved to Wickenby, Lincolnshire with Tempest Two Limited. In 2016, it moved to Dunmow, Essex with Anglia Aircraft Restorations Ltd, where it was being restored from 2016, until 2019 when it moved to Air Leasing at Sywell Aerodrome in Northampton for its final stages of restoration. It had its maiden flight from its home base at Sywell Aerodrome on 10 October 2023 after a 34-year-long restoration.[80]

Under restoration/privately owned

[edit]- Mk.II MW404 - under restoration to fly by Chris Miller, Texas, USA[81]

- Mk.II MW810 - under restoration to fly with Nelson Ezell, Texas, USA[82]

- Mk.V N7027E/EJ693 - under restoration to fly for Kermit Weeks, USA[83]

- Mk.V G-TMPV/JN768 - owned by Richard Grace, Halstead, UK, bought by Hawker Typhoon Preservation Group for incorporating into RB396[84][85]

- Mk.II MW376 - under restoration to fly by KF Aerospace, Kelowna, B.C., Canada [86]

Stored

[edit]On display

[edit]- Mk.II MW758/HA580 - On display at South Wales Aviation Museum, St Athan, Wales, UK

- Mk.II HA623/MW848 - Indian Air Force Museum, New Delhi, India[89]

- Mk.II PR536 - Royal Air Force Museum Cosford, Cosford, UK[90]

- TT.5 NV778 - Royal Air Force Museum London, Hendon, UK[91]

Specifications (Tempest Mk.V)

[edit]

Data from Jane's all the World's Aircraft 1947,[92] Jane's Fighting Aircraft of World War II,[55] Jane's all the World's Aircraft 1946,[93] The Hawker Tempest I-IV[94]

General characteristics

- Crew: 1

- Length: 33 ft 8 in (10.26 m) [v 1]

- Wingspan: 41 ft 0 in (12.50 m)

- Height: 14 ft 10 in (4.52 m) tail in rigging position with one propeller blade vertical)[f][v 2]

- Wing area: 302 sq ft (28.1 m2)

- Airfoil: root: Hawker H.14/14/37.5 ; tip: Hawker H.14/10/37.5 (maximum thickness at 37.5% chord)

- Gross weight: 11,400 lb (5,171 kg) as interceptor[g][v 3]

- Fuel capacity: 160 imp gal (190 US gal; 730 L) internal with optional 90 imp gal (110 US gal; 410 L) or 180 imp gal (220 US gal; 820 L) in two drop tanks under wings

- Oil tank capacity: 16 imp gal (19 US gal; 73 L)[v 4]

- Powerplant: 1 × Napier Sabre IIB H-24 liquid-cooled sleeve-valve piston engine, 2,420 hp (1,800 kW) at +11 lb boost for 5 minutes at sea level[nb 12][h][v 5]

- Propellers: 4-bladed de Havilland Hydromatic, 14 ft (4.3 m) diameter constant-speed propeller[v 6]

Performance

- Maximum speed: 435 mph (700 km/h, 378 kn) at 17,000 ft (5,200 m)[i][v 7]

- Combat range: 420 mi (680 km, 360 nmi) [v 8]

- Service ceiling: 36,500 ft (11,100 m)

- Rate of climb: 4,700 ft/min (24 m/s)

- Time to altitude: 20,000 ft (6,100 m) in 6 minutes at combat power[v 9]

- Wing loading: 44.7 lb/sq ft (218 kg/m2) at 13,500 lb (6,100 kg)

- Power/mass: 0.149 hp/lb (0.245 kW/kg) at 13,500 lb (6,100 kg)[v 10]

Armament

- 4 × 20 mm (0.787 in) Mark II Hispano cannon, 200 rpg.[j].

- with

- 2 × 500 lb (230 kg) or 1,000 lb (450 kg) bombs

- 8 × 3 in (76.20 mm) RP-3 rockets (post-Second World War)

- Provision for 2 × 45 imp gal (54 US gal; 200 L) or 2 × 90 imp gal (110 US gal; 410 L) drop tanks.

Variants

- ^ Tempest II: 34 ft 5 in (10.49 m)

- ^ Tempest II:13 ft 6 in (4.11 m) (tail in rigging position with one propeller blade vertical) ; 14 ft 6 in (4.42 m) (tail down with one propeller blade vertical)

- ^ Tempest II: 11,800 lb (5,400 kg) (interceptor) ; 12,800 lb (5,800 kg) (fighter-bomber: 2x 500 lb (230 kg) bombs) ; 13,800 lb (6,300 kg) (fighter-bomber: 2x 1,000 lb (450 kg) bombs), Tempest VI: 12,000 lb (5,400 kg) (interceptor)

- ^ Tempest II: 14 imp gal (17 US gal; 64 L), Tempest VI: 22 imp gal (26 US gal; 100 L)

- ^ Tempest II: Bristol Centaurus V 2,530 hp (1,890 kW) for 5 minutes at sea level, Tempest VI: Napier Sabre V 2,420 hp (1,800 kW) for 5 minutes at sea level

- ^ Tempest II: Rotol 12 ft 9 in (3.89 m) diameter 4-bladed constant-speed propeller

- ^ Tempest II: 440 mph (380 kn; 710 km/h) at 17,000 ft (5,200 m) ; 410 mph (360 kn; 660 km/h) at 29,000 ft (8,800 m) ; 400.6 mph (348.1 kn; 644.7 km/h) at sea level, Tempest VI: 450 mph (390 kn; 720 km/h) at 14,500 ft (4,400 m) ; 425 mph (369 kn; 684 km/h) at 30,000 ft (9,100 m) ; 395 mph (343 kn; 636 km/h) at sea level

- ^ Tempest II: with 250 imp gal (300 US gal; 1,100 L) fuel, climb, 15 minutes combat and RTB with 20% reserve

- ^ Tempest II: 20,000 ft (6,100 m) in 5 minutes at combat power, Tempest VI: 20,000 ft (6,100 m) in 4 minutes 45 seconds at combat power

- ^ Tempest II: 0.196 hp/lb (0.322 kW/kg) at 13,300 lb (6,000 kg), Tempest VI: 0.192 hp/lb (0.316 kW/kg) at 12,000 lb (5,400 kg)

See also

[edit]Related development

Aircraft of comparable role, configuration, and era

- Lavochkin La-7

- Messerschmitt Bf 109

- Nakajima Ki-84

- North American P-51 Mustang

- Republic P-47 Thunderbolt

- Supermarine Spitfire

- Vought F4U Corsair

- Focke-Wulf Ta 152

Related lists

- List of aircraft of the Royal Air Force

- List of aircraft of the Royal New Zealand Air Force and Royal New Zealand Navy

- List of aircraft of the United Kingdom in World War II

- List of aircraft of World War II

References

[edit]Footnotes

[edit]- ^ Both the Spitfire and the Typhoon were designed when little was known about the behaviour of air at high subsonic Mach numbers, and of what would later become known as the Critical Mach number. The importance of this to high speed, high altitude flight would be discovered during combat in the Battle of Britain, where the Spitfire's thinner wing gave it an advantage at higher altitudes over the thicker wing-sectioned Hurricane, which was affected to a greater extent by compressibility. Fortuitously, the Spitfire had been designed with a thin wing that was subsequently discovered by the RAE to possess a high Critical Mach No.

- ^ Camm later remarked: "The Air Staff wouldn't buy anything that didn't look like a Spitfire."[citation needed]

- ^ The renaming of the "Typhoon II" to "Tempest" was considered to be an indication of the level of changes and increasing number of refinements that had made the two aircraft more unique and distinguished from one another.[11]

- ^ The use of wing radiators was a point of controversy, with Air Ministry officials approaching Camm with doubts concerning its vulnerability to battle damage.[20]

- ^ LA610 went on to serve as the prototype for the later Hawker Fury/Sea Fury, what would be the ultimate offshoot of the Typhoon and Tempest family as well as the fastest of all Hawker-built piston-engine fighters.[21]

- ^ It had been intended that prefabricated Typhoon components could be reused on the Tempest, this proved to be impractical as the design production Tempest had diverged considerably from the Typhoon.[20]

- ^ Although JNxxx serialled Tempest Vs are called "Series 1" and later ones called "Series 2", these definitions first appeared in 1957, and there is room for doubt about them being used by Hawker during the Second World War.[28]

- ^ LA607 was presented to the College of Aeronautics at Cranfield, Bedfordshire and is currently (As of 2011[update]) preserved at Fantasy of Flight at Polk city, Florida.

- ^ According to Roland Beamont, these production delays had been caused by an industrial dispute at Langley.[citation needed]

- ^ As well as the flak guns, there were several piston engine fighter units based in the area which were tasked to cover the jets as they were landing.

- ^ The wings were capable of mounting later 20 mm Hispano Mk. V guns and Series 1 individuals might have received such with time.[34]

- ^ Sabre IIB gave 2,420 hp (1,804 kW) at +11 lb boost at sea level, 3,850 rpm.

- ^ Buttler gives 6 August as the official renaming, and notes the suggestion came from Camm in January.[13]

- ^ At the start of March 1942, the contract had been for 400 Mark I[26]

- ^ The weapon has been misidentified as a 40 mm cannon in many references, such as Mason 1991.[40]

- ^ Vickers, Rolls-Royce and the War Office Design Department produced competing designs but Rolls Royce stopped work before completing a weapon[38]

- ^ post war, the RAF changed to using Roman numerals in designations

- ^ 16 ft 1 in (4.90 m) (tail down with one propeller blade vertical)

- ^ 12,500 lb (5,700 kg) with 2x 500 lb (230 kg) bombs; 13,500 lb (6,100 kg) with 2x 1,000 lb (450 kg) bombs

- ^ 2,010 hp (1,500 kW) for take-off ; 2,045 hp (1,525 kW) at 13,750 ft (4,190 m)

- ^ 390 mph (340 kn; 630 km/h) at sea level

- ^ Later models used Mark V Hispano cannon

Citations

[edit]- ^ Mason 1967, pp. 14, 16.

- ^ Beamont, Roland. Tempest over Europe, 1994, p. 13.

- ^ Thomas and Shores 1988, pp. 18, 105.

- ^ a b Mason 1967, pp. 3–4.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Thomas and Shores 1988, p. 105.

- ^ J. A. D. Ackroyd. "The Spitfire Wing Planform: A Suggestion." Journal of Aeronautical History, Paper No. 2013/02.

- ^ a b c d Mason 1967, p. 3.

- ^ Tempest V Pilot's Notes 1944, pp. 6–7, 31.

- ^ Bentley 1973, p. 95.

- ^ a b c Thomas and Shores 1988, p. 106.

- ^ a b c d e f g Mason 1967, p. 4.

- ^ a b c d e Buttler 2004 p18

- ^ Buttler 2004 p18

- ^ a b c d Mason 1967, pp. 4-6.

- ^ Buttler 2004 p18

- ^ a b c Mason 1991, p. 331.

- ^ a b Mason 1967, pp. 4–5.

- ^ a b c d e f "Tempest Mark II (F.2)". hawkertempest.se. Retrieved 10 August 2021.

- ^ "HAWKER'S FASTEST FURY – LA610". navalairhistory.com. 21 February 2018. Retrieved 14 August 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g Mason 1967, p. 5.

- ^ a b c d e f Mason 1967, p. 6.

- ^ a b Mason 1991, p. 332.

- ^ Buttler 2004 p21

- ^ Buttler, 2004 p 20

- ^ a b c d e Thomas and Shores 1988, p. 107.

- ^ Buttler 2004 p 20

- ^ a b Ovčáčík and Susa 2000, p. 1.

- ^ "Discussion on first 100 Tempest V." rafcommands.com. Retrieved: 1 January 2012.

- ^ Mason 1991, p. 333.

- ^ a b Bentley 1973, pp. 92–93.

- ^ a b Ovčáčík and Susa 2000, pp. 2, 4.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Mason 1967, p. 7.

- ^ Mason 1991, p. 334.

- ^ a b c d e f "Tempest Armament/Drop tanks". hawkertempest.se. Retrieved 10 August 2021.

- ^ Ovčáčík and Susa 2000, p. 30.

- ^ Flight 1946, p. 91.

- ^ Thomas and Shores 1988, p. 112.

- ^ a b c d Williams, A. G. "The RAF'S 47 mm Class P Gun Project". quarry.nildram.co.uk. Archived from the original on 19 March 2016. Retrieved 16 March 2012.

- ^ Mason 1967, p. 13.

- ^ Mason 1991, p. 336.

- ^ http://i.imgur.com/brlZOwU.png [bare URL image file]

- ^ Mason 1991, p. 337.

- ^ a b c d e f Mason 1967, p. 11.

- ^ Mason 1991, p. 339.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Mason 1967, p. 12.

- ^ a b c Ovčáčík and Susa 2000, p. 2.

- ^ Mason 1967, pp. 11-12.

- ^ a b c Ovčáčík and Susa 2000, pp. 2, 7–8.

- ^ a b Mason 1991, p. 342.

- ^ a b Mason 1991, p. 340.

- ^ a b Buttler 2004, p. 30.

- ^ Thomas and Shores 2008, p. 584.

- ^ Ovčáčík and Susa 2000, p. 3.

- ^ a b c Ovčáčík and Susa 2000, p. 4.

- ^ a b "Tempest MK V Performance." wwiiaircraftperformance.org. Retrieved: 10 August 2010.

- ^ "Undercarriage blueprint." Archived 2008-03-26 at the Wayback Machine hawkertempest.se. Retrieved: 1 January 2012.

- ^ Shores and Thomas 2008, p. 679.

- ^ "4-Cannon Tempest Chases Nazi Robot Bomb." Popular Mechanics, February 1945.

- ^ Mason 1967, p. 7, 10.

- ^ a b Mason 1967, p. 10.

- ^ a b Shores and Thomas 2008, p. 678.

- ^ a b Thomas Shores and Thomas 2008, p. 585.

- ^ Air Ministry 1944, p. 16.

- ^ Mason 1967, pp. 10–11.

- ^ a b Shores and Thomas 2008, pp. 679, 684, 686.

- ^ Shores 2006 pp497–498

- ^ Clostermann, 2004 pp.273–274

- ^ "Hawker Tempest." hawkertempest.se. Retrieved: 1 January 2012.

- ^ Clostermann 2004, p. 250.

- ^ "Fluglehrzentrum F-4F JG 72, JBG 36" [F-4F Flight Training Center Jagdgeschwader 72 "Westfalen" Fighter-Bomber Wing 36]. etnp.de (in German). Archived from the original on 5 January 2016. Retrieved 5 January 2016.

- ^ "The "Westfalen-Wing" in Rheine-Hopsten." etnep.de. Retrieved: 1 January 2012.

- ^ Thomas and Shores 1988, p. 129.

- ^ from tables in The Typhoon & Tempest Story, Thomas & Shores, Arms & Armour, 1988

- ^ "Tempest Victories". The Hawker Tempest Page.

- ^ Thomas and Shores 1988, p. 193.

- ^ a b c d "Tempest Mark III (F.3)". hawkertempest.se. Retrieved 10 August 2021.

- ^ a b c "Tempest Mark V (F.5)". hawkertempest.se. Retrieved 10 August 2021.

- ^ "Tempest Mark VI (F.6)". hawkertempest.se. Retrieved 10 August 2021.

- ^ "Hawker Tempest." rcaf.com. Retrieved: 3 November 2009.

- ^ "Sywell Aviation Museum on Facebook". Sywell Aviation Museum.

- ^ "MW404". Hawkertempest.se. Archived from the original on 12 November 2014. Retrieved 26 November 2014.

- ^ "MW810". Hawkertempest.se. Archived from the original on 12 November 2014. Retrieved 26 November 2014.

- ^ "EJ693". Hawkertempest.se. Archived from the original on 12 November 2014. Retrieved 26 November 2014.

- ^ "HAWKER TEMPEST MK V". Caa.co.uk. Archived from the original on 22 May 2014. Retrieved 26 November 2014.

- ^ "JN768". Hawker Tempest.

- ^ "MW376". Hawkertempest.se.

- ^ "LA607". Hawkertempest.se. Archived from the original on 12 November 2014. Retrieved 26 November 2014.

- ^ "Summary". Hawkertempest.se. Retrieved 26 November 2014.

- ^ http://hawkertempest.se/index.php/survivors/ha62323 [dead link]

- ^ "PR536". Hawkertempest.se. Archived from the original on 12 November 2014. Retrieved 26 November 2014.

- ^ "NV778". Hawkertempest.se. Archived from the original on 12 November 2014. Retrieved 26 November 2014.

- ^ Bridgman, Leonard, ed. (1947). Jane's all the World's Aircraft 1947. London: Sampson Low, Marston & Co. pp. 57c–59c.

- ^ Bridgman 1946, pp. 126–127.

- ^ Mason 1967, p. 16.

Bibliography

[edit]- Beamont, Roland. My Part of the Sky. London, UK: Patrick Stephens, 1989. ISBN 1-85260-079-9.

- Beamont, Roland. Tempest over Europe. London, UK: Airlife, 1994. ISBN 1-85310-452-3.

- Beamont, Roland. "Tempest Summer: part 1" Aeroplane Monthly, June 1992.

- Bentley, Arthur L. "Hawker Tempest Article and Drawings." Scale Models Magazine Vol. 4, No 2. February 1973. Hemel Hempstead, Hertfordshire, UK.

- Bridgman, Leonard (ed.). "The Hawker Tempest." Jane's Fighting Aircraft of World War II. London: Studio, 1946. ISBN 1-85170-493-0.

- Brown, Charles E. Camera Above the Clouds Volume 1. Shrewsbury, UK: Airlife Publishing, 1988. ISBN 0-906393-31-0.

- Buttler, Tony. British Secret Projects: Fighters and Bombers 1935–1950. Hinckley: Midland, 2004. ISBN 1-85780-179-2.

- Clostermann, Pierre. The Big Show. London, UK: Cassell Military Paperbacks, 2004. ISBN 1-4072-2200-4 Parameter error in {{ISBN}}: checksum.

- Darling, Kev. Hawker Typhoon, Tempest and Sea Fury. Ramsgate, Marlborough, Wiltshire, UK: The Crowood Press Ltd., 2003. ISBN 1-86126-620-0.

- Halliday, Hugh A. Typhoon and Tempest: the Canadian Story. Charlottesville, Virginia: Howell Press, 2000. ISBN 0-921022-06-9.

- Jackson, Robert Hawker Tempest and Sea Fury. London: Blandford Press, 1989. ISBN 0-7137-1684-3.

- Mason, Francis K. Hawker Aircraft Since 1920 (3rd revised edition). London: Putnam, 1991. ISBN 0-85177-839-9.

- Mason, Francis K. The Hawker Typhoon and Tempest. Bourne End, Buckinghamshire, UK: Aston Publications, 1988. ISBN 0-946627-19-3.

- Mason, Francis K. The Hawker Tempest I–IV (Aircraft in Profile Number 197). Leatherhead, Surrey, UK: Profile Publications Ltd., 1967.

- "Napier Flight Development". Flight. Vol. L, no. 1961. 25 July 1946. Archived from the original on 5 March 2016..

- Ovčáčík, Michal and Karel Susa. Hawker Tempest: MK I, V, II, VI, TT Mks.5,6. (World War IT Wings Line) Prague, Czech Republic: 4+ Publications, 2000. ISBN 80-902559-2-2.

- Pilot's Notes for Hawker Tempest V: Air Publication 2458c. London: Air Ministry, 1944.

- Rawlings, John D. R. Fighter Squadrons of the RAF and their Aircraft. Somerton, UK: Crécy Books, 1993. ISBN 0-947554-24-6.

- Reed, Arthur and Roland Beamont. Typhoon and Tempest at War. Shepperton, Surrey, UK: Ian Allan, 1974. ISBN 0-7110-0542-7.

- Scutts, Jerry. Typhoon/Tempest in Action (Aircraft in Action series, No. 102). Carrollton, Texas: Squadron/Signal Publications, 1990. ISBN 978-0-89747-232-6.

- Shores, Christopher. Ground Attack Aircraft of World War Two. London: Macdonald and Jane's, 1977. ISBN 0-356-08338-1.

- Tempest at War DVD, IWM Footage.

- Shores, Christopher (2006). 2nd Tactical Air Force. Volume III: From the Rhine to Victory: January to May 1945. Classic Publications. ISBN 1903223601.

- Thomas, Chris. Typhoon and Tempest Aces of World War 2. Botley, Oxford, UK: Osprey Publishing, 1999. ISBN 1-85532-779-1.

- Thomas, Chris and Christopher Shores. The Typhoon and Tempest Story. London: Arms and Armour Press, 1988. ISBN 978-0-85368-878-5.

- Watkins, David and Phil Listemann. No. 501 (County of Gloucester) Squadron 1939–1945: Hurricane, Spitfire, Tempest. Boé Cedex, France: Graphic Sud, 2007. ISBN 978-2-9526381-3-5.

Further reading

[edit]- Shores, Christopher and Chris Thomas. Second Tactical Air Force Volume One: Spartan to Normandy, June 1943 to June 1944. Hersham, Surrey, UK: Ian Allan Publishing Ltd., 2004. ISBN 1-903223-40-7.

- Shores, Christopher and Chris Thomas. Second Tactical Air Force Volume Two: Breakout to Bodenplatte, July 1944 to January 1945. Hersham, Surrey, UK: Ian Allan Publishing Ltd., 2005. ISBN 1-903223-41-5.

- Shores, Christopher and Chris Thomas. Second Tactical Air Force Volume Three: From the Rhine to Victory, January to May 1945. Hersham, Surrey, UK: Ian Allan Publishing Ltd., 2006. ISBN 1-903223-60-1.

- Shores, Christopher and Chris Thomas. Second Tactical Air Force Volume Four: Squadrons, Camouflage and Markings, Weapons and Tactics 1943–1945. Hersham, Surrey, UK: Ian Allan Publishing Ltd., 2008. ISBN 978-1-906537-01-2

External links

[edit]- "The Hawker Typhoon, Tempest, & Sea Fury"

- The Hawker Tempest Page

- Hawker Tempest V Performance

- U.S. report on Tempest V

- Hawker Tempest profile, walkaround video, technical details for each Mk and photos

- "Spinning Intake – Ingenious Napier Development of Sabre-Tempest Annular Radiator Installation," – A 1946 Flight article on the annular radiator version of the Tempest