Videotelephony

This article's lead section may be too short to adequately summarize the key points. (November 2024) |

Videotelephony (also known as videoconferencing or video calling) is the use of audio and video for simultaneous two-way communication.[1] Today, videotelephony is widespread. There are many terms to refer to videotelephony. Videophones are standalone devices for video calling (compare Telephone). In the present day, devices like smartphones and computers are capable of video calling, reducing the demand for separate videophones. Videoconferencing implies group communication.[2] Videoconferencing is used in telepresence, whose goal is to create the illusion that remote participants are in the same room.

The concept of videotelephony was conceived in the late 19th century, and versions were available to the public starting in the 1930s. Early demonstrations were installed at booths in post offices and shown at various world expositions. In 1970, AT&T launched the first commercial personal videotelephone system. In addition to videophones, there existed image phones which exchanged still images between units every few seconds over conventional telephone lines. The development of advanced video codecs, more powerful CPUs, and high-bandwidth Internet service in the late 1990s allowed digital videophones to provide high-quality low-cost color service between users almost any place in the world.

Applications of videotelephony include sign language transmission for deaf and speech-impaired people, distance education, telemedicine, and overcoming mobility issues. News media organizations have used videotelephony for broadcasting.[citation needed]

History

[edit]

Origin

[edit]The concept of videotelephony was first conceived in the late 1870s, both in the United States and in Europe, although the basic sciences to permit its very earliest trials would take nearly a half century to be discovered.[citation needed] The prerequisite knowledge arose from intensive research and experimentation in several telecommunication fields, notably electrical telegraphy, telephony, radio, and television.

Early systems

[edit]Simple analog videophone communication could be established as early as the invention of the television. Such an antecedent usually consisted of two closed-circuit television systems connected via coax cable or radio. An example of that was the German Reich Postzentralamt (post office) videotelephone network serving Berlin and several German cities via coaxial cables between 1936 and 1940.[3][4]

The development of videotelephony as a subscription service started in the latter half of the 1920s in the United Kingdom and the United States, spurred notably by John Logie Baird and AT&T's Bell Labs. This occurred in part, at least with AT&T, to serve as an adjunct supplementing the use of the telephone. A number of organizations believed that videotelephony would be superior to plain voice communications. Attempts at using normal telephony networks to transmit slow-scan video, such as the first systems developed by AT&T Corporation, first researched in the 1950s, failed mostly due to the poor picture quality and the lack of efficient video compression techniques.

During the first crewed space flights, NASA used two radio-frequency (UHF or VHF) video links, one in each direction. TV channels routinely use this type of videotelephony when reporting from distant locations. The news media were to become regular users of mobile links to satellites using specially equipped trucks, and much later via special satellite videophones in a briefcase. This technique was very expensive, though, and was not adopted for applications such as telemedicine, distance education, and business meetings.

Decades of research and development culminated in the 1970 commercial launch of AT&T's Picturephone service, available in select cities. However, the system was a commercial failure, chiefly due to consumer apathy, high subscription costs, and lack of network effect—with only a few hundred Picturephones in the world, users had extremely few contacts they could actually call, and interoperability with other videophone systems would not exist for decades.

Digital

[edit]In the 1980s, digital telephony transmission networks became possible, such as with ISDN networks. During this time, there was also research into other forms of digital video and audio communication. Many of these technologies, such as the Media space, are not as widely used today as videoconferencing but were still an important area of research.[5][6] The first dedicated systems started to appear as ISDN networks were expanding throughout the world. One of the first commercial videoconferencing systems sold to companies came from PictureTel Corp., which had an initial public offering in November, 1984.

In 1984, Concept Communication in the United States created a circuit board for standard personal computers that doubled the video frame rate of typical digital videotelephone systems from 15 to 30 frames per second, and reduced the cost from $100,000 to $12,000.[7] The company also secured a patent for a codec for full-motion videoconferencing, first demonstrated at AT&T Bell Labs in 1986.[7][8]

Very expensive videoconferencing systems continued to rapidly evolve throughout the 1980s and 1990s. Proprietary equipment, software, and network requirements gave way to standards-based technologies that were available for anyone to purchase at a reasonable cost.

While videoconferencing technology was initially used primarily within internal corporate communication networks, one of the first community service uses of the technology started in 1992 through a unique partnership with PictureTel and IBM, which at the time were promoting a jointly developed desktop based videoconferencing product known as the PCS/1. Over the next 15 years, Project DIANE (Diversified Information and Assistance Network) grew to use a variety of videoconferencing platforms to create a multi-state cooperative public service and distance education network consisting of several hundred schools, libraries, science museums, zoos and parks, and many other community-oriented organizations.[citation needed]

Transition to internet and mobile devices

[edit]Advances in video compression allowed digital video streams to be transmitted over the Internet, which was previously difficult due to the impractically high bandwidth requirements of uncompressed video. The DCT algorithm was the basis for the first practical video coding standard that was useful for online videoconferencing, H.261, standardised by the ITU-T in 1988, and subsequent H.26x video coding standards.[9]

In 1992 CU-SeeMe was developed at Cornell by Tim Dorcey et al. In 1995 the first public videoconference between North America and Africa took place, linking a technofair in San Francisco with a techno-rave and cyberdeli in Cape Town. At the 1998 Winter Olympics opening ceremony in Nagano, Japan, Seiji Ozawa conducted the Ode to Joy from Beethoven's Ninth Symphony simultaneously across five continents in near-real-time.

Kyocera conducted a two-year development campaign from 1997 to 1999 that resulted in the release of the VP-210 Visual Phone, the first mobile colour videophone that also doubled as a camera phone for still photos.[10][11] The camera phone was the same size as similar contemporary mobile phones, but sported a large camera lens and a 5 cm (2 inch) colour TFT display capable of displaying 65,000 colors, and was able to process two video frames per second.[11][12]

Videotelephony was popularized in the 2000s via free Internet services such as Skype and iChat, web plugins supporting H.26x video standards, and online telecommunication programs that promoted low cost, albeit lower quality, videoconferencing to virtually every location with an Internet connection.

Videotelephony became even more widespread through the deployment of video-enabled mobile phones such as 2010s iPhone 4, plus videoconferencing and computer webcams which use Internet telephony. In the upper echelons of government, business, and commerce, telepresence technology, an advanced form of videoconferencing, has helped reduce the need to travel.[citation needed]

Additional history

[edit]In May 2005, the first high definition videoconferencing systems, produced by Lifesize, were displayed at the Interop trade show in Las Vegas, Nevada, able to provide video at 30 frames per second with a 1280 by 720 display resolution.[13][14] Polycom introduced its first high definition videoconferencing system to the market in 2006. As of the 2010s, high-definition resolution for videoconferencing became a popular feature, with most major suppliers in the videoconferencing market offering it.

Technological developments by videoconferencing developers in the 2010s have extended the capabilities of videoconferencing systems beyond the boardroom for use with hand-held mobile devices that combine the use of video, audio and on-screen drawing capabilities broadcasting in real time over secure networks, independent of location. Mobile collaboration systems now allow people in previously unreachable locations, such as workers on an offshore oil rig, the ability to view and discuss issues with colleagues thousands of miles away. Traditional videoconferencing system manufacturers have begun providing mobile applications as well, such as those that allow for live and still image streaming.[15]

The highest ever video call (other than those from aircraft and spacecraft) took place on May 19, 2013, when British adventurer Daniel Hughes used a smartphone with a BGAN satellite modem to make a videocall to the BBC from the summit of Mount Everest, at 8,848 metres (29,029 ft) above sea level.[16]

The COVID-19 pandemic resulted in a significant increase in the use of videoconferencing. Berstein Research found that Zoom added more subscribers during the first two months of 2020 alone than in the entire year 2019. GoToMeeting had a 20 percent increase in usage, according to LogMeIn.[17] UK based StarLeaf reported a 600 percent increase in national call volumes.[18] Videoconferencing became so widespread during the pandemic that the term Zoom fatigue came to prominence, referring to the taxing nature of spending long periods of time on videocalls.[19] This fatigue refers to the psychological and physiological effects participants involved in videoconferencing.[20][21][22] One experimental study from 2021 revealed a link between camera use in videoconferencing and a prediction of fatigue occurrence an individual.[23][24] Furthermore, a 2022 article in the journal "Computers in Human Behaviour" highlighted a study linking negative attitudes with the use of "self-view" when videoconferencing.[25][26]

On 21 September 2021, Facebook launched two new versions of its Portal video-calling devices, the Portal Go and Portal Plus. The new video calling devices include the first portable variety of the hardware and number of updates.[27]

Major categories

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (April 2024) |

Videotelephony can be categorized by its functionality and intended purpose, and also by its method of transmission.

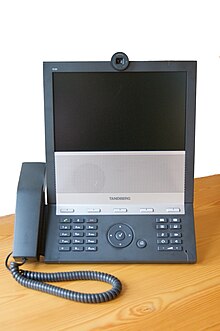

Videophones were the earliest form of videotelephony, dating back to initial tests in 1927 by AT&T. During the late 1930s, the post offices of several European governments established public videophone services for person-to-person communications using dual cable circuit telephone transmission technology. In the present day, standalone videophones and UMTS video-enabled mobile phones are usually used on a person-to-person basis.

Videoconferencing saw its earliest use with AT&T's Picturephone service in the early 1970s. Transmissions were analog over short distances, but converted to digital forms for longer calls, again using telephone transmission technology. Popular corporate video-conferencing systems in the present day have migrated almost exclusively to digital ISDN and IP transmission modes due to the need to convey the very large amounts of data generated by their cameras and microphones. These systems are often intended for use in conference mode, that is by many people in several different locations, all of whom can be viewed by every participant at each location.

Telepresence systems are a newer, more advanced subset of videoconferencing systems, meant to allow higher degrees of video and audio fidelity. Such high-end systems are typically deployed in corporate settings.

Mobile collaboration systems are another recent development, combining the use of video, audio, and on-screen drawing capabilities using newest generation hand-held electronic devices broadcasting over secure networks, enabling multi-party conferencing in real time, independent of location. Proximity chat is another alternative mode, focused on the flexibility of small group conversations.

A more recent technology encompassing these functions is TV cams. TV cams enable people to make video calls using video calling services, like Skype on their TV, without using a PC connection. TV cams are specially designed video cameras that feed images in real time to another TV camera or other compatible computing devices like smartphones, tablets and computers.

Webcams are popular, relatively low-cost devices that can provide live video and audio streams via personal computers, and can be used with many software clients for both video calls and videoconferencing.[28]

Each of the systems has its own advantages and disadvantages, including video quality, capital cost, degrees of sophistication, transmission capacity requirements, and cost of use.

By cost and quality of service

[edit]From the least to the most expensive systems:

- Web camera videophone and videoconferencing systems, either stand-alone or built-in, that serve as complements to personal computers, connected to other participants by computer and VoIP networks—lowest direct cost, assuming the users already possess computers at their respective locations. Quality of service can range from low to very high, including high definition video available on the latest model webcams. A related and similar device is a TV camera which is usually small, sits on top of a TV, and can connect to it via its HDMI port, similar to how a webcam attaches to a computer via a USB port.

- Videophones—low to midrange cost. The earliest standalone models operated over either plain old telephone service (POTS) lines on the PSTN telephone networks or more expensive ISDN lines, while newer models have largely migrated to Internet Protocol line service for higher image resolutions and sound quality. Quality of service for standalone videophones can vary from low to high;

- Huddle room or all-in-one systems —low to midrange cost, newer endpoint category based on standard videoconferencing systems, but defined by the camera, microphone(s), speakers, and codec contained in a single piece of hardware. Typically used in small to medium spaces where beamforming microphone arrays located in the system are sufficient, in lieu of table or ceiling microphones in closer proximity to the in-room participants. Quality of service is comparable to standard videoconferencing systems, varying from moderate to high. Some manufacturers' huddle room systems do not include the codec within the soundbar-shaped unit, rather only camera, microphone, and speakers. These systems are usually still classified as huddle room systems, but, like webcams, rely on a USB connection to an external device, usually a PC, to process the video codec responsibilities. Despite its name, video conferencing systems for Huddle Rooms prevent participants from huddling close together to be seen in the camera. All-in-one systems for these types of rooms range from wide angles such as 110° Horizontal field of view (FOV) to as much as 360° FOV that allow a full view of the room.

- Videoconferencing systems—midrange cost, usually using multipoint control units or other bridging services to allow multiple parties on videoconference calls. Quality of service can vary from moderate to high.

- Telepresence systems—highest capabilities and highest cost. Full high-end systems can involve specially built teleconference rooms to allow expansive views with very high levels of audio and video fidelity, to permit an 'immersive' videoconference. When the proper type and capacity transmission lines are provided between facilities, the quality of service reaches state-of-the-art levels.

Security concerns

[edit]Computer security experts have shown that poorly configured or inadequately supervised videoconferencing systems can permit an easy virtual entry by computer hackers and criminals into company premises and corporate boardrooms.[29]

Adoption

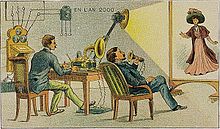

[edit]For over a century, futurists have envisioned a future where telephone conversations will take place as actual face-to-face encounters with video as well as audio. Sometimes it is simply not possible or practical to have face-to-face meetings with two or more people. Sometimes a telephone conversation or conference call is adequate. Other times, e-mail exchanges are adequate. However, videoconferencing adds another option and can be considered when:

- A live conversation is needed

- Non-verbal (visual) information is an important component of the conversation

- The parties of the conversation cannot physically come to the same location

- The expense or time of travel is a consideration

Bill Gates said in 2001 that he used videoconferencing "three or four times a year", because digital scheduling was difficult and "if the overhead is super high, then you might as well just have a face-to-face meeting".[30] Some observers argue that three outstanding issues have prevented videoconferencing from becoming a widely adopted form of communication, despite the ubiquity of videoconferencing-capable systems.[31]

- Eye contact: Eye contact plays a large role in conversational turn-taking, perceived attention and intent, and other aspects of group communication.[32] While traditional telephone conversations give no eye contact cues, many videoconferencing systems are arguably worse in that they provide an incorrect impression that the remote interlocutor is avoiding eye contact. Some telepresence systems have cameras located in the screens that reduce the amount of parallax observed by the users. This issue is also being addressed through research that generates a synthetic image with eye contact using stereo reconstruction.[33]

Telcordia Technologies, formerly Bell Communications Research, owns a patent for eye-to-eye videoconferencing using rear projection screens with the video camera behind it, evolved from a 1960s U.S. military system that provided videoconferencing services between the White House and various other government and military facilities. This technique eliminates the need for special cameras or image processing.[34] - Appearance consciousness: A second psychological problem with videoconferencing is being on camera, with the video stream possibly even being recorded. The burden of presenting an acceptable on-screen appearance is not present in audio-only communication. Early studies by Alphonse Chapanis found that the addition of video actually impaired communication, possibly because of the consciousness of being on camera.[35]

- Signal latency: The information transport of digital signals in many steps need time. In a telecommunicated conversation, an increased latency (time lag) larger than about 150–300 ms becomes noticeable and is soon observed as unnatural and distracting. Therefore, next to a stable large bandwidth, a small total round-trip time is another major technical requirement for the communication channel for interactive videoconferencing.[36]

- Bandwidth and quality of service: In some countries, it is difficult or expensive to get a high-quality connection that is fast enough for good-quality videoconferencing. Technologies such as ADSL are usually provided as two separate lines (for uplink/downlink) because each has limited upload speeds and cannot upload and download simultaneously at full speed. As Internet speeds increase, higher quality and high-definition videoconferencing will become more readily available.

- Complexity of systems: Most users are not technically experienced and want a simple interface. In hardware systems, an unplugged cord or an unresponsive remote control is seen as a failure, contributing to a perceived unreliability. Successful systems are backed by support teams who can provide fast assistance when required.

- Perceived lack of interoperability: Not all systems can readily interconnect; for example, ISDN and IP systems require a gateway. Popular software solutions cannot easily connect to hardware systems. Some systems use different standards, features, and qualities which can require additional configuration when connecting to dissimilar systems. Free software systems circumvent this limitation by making it relatively easy for a single user to communicate over multiple incompatible platforms.

- Expense of commercial systems: Well-designed telepresence systems require specially designed rooms which can cost hundreds of thousands of dollars to fit out their rooms with codecs, integration equipment (such as Multipoint Control Units), high fidelity sound systems, and furniture. Monthly charges may also be required for bridging services and high-capacity broadband service.

These are some of the reasons many organizations only use the systems internally, where there is less risk of loss of customers. An alternative for those lacking dedicated facilities is the rental of videoconferencing-equipped meeting rooms in cities around the world. Clients can book rooms and turn up for the meeting, with all technical aspects being prearranged and support being readily available if needed. The issue of eye contact may be solved with advancing technology, including smartphones which have the screen and camera in essentially the same place. In developed countries, the near-ubiquity of smartphones, tablet computers, and computers with built-in audio and webcams removes the need for expensive dedicated hardware.

Technology

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (February 2013) |

Components and types

[edit]

The core technology used in a videotelephony system is digital compression of audio and video streams in real time. The hardware or software that performs compression is called a codec (coder/decoder). Compression rates of up to 1:500 can be achieved. The resulting digital stream of 1s and 0s is subdivided into labeled packets, which are then transmitted through a digital network of some kind (usually ISDN or IP).

The other components required for a videoconferencing system include:

- Video input: (PTZ / 360° / Fisheye) video camera, or webcam

- Video output: computer monitor, television, or projector

- Audio input: microphones, CD/DVD player, cassette player, or any other source of PreAmp audio outlet.

- Audio output: usually loudspeakers associated with the display device or telephone

- Data transfer: analog or digital telephone network, LAN, or Internet

- Computer: a data processing unit that ties together the other components, does the compressing and decompressing, and initiates and maintains the data linkage via the network.

There are basically three kinds of videoconferencing and videophone systems:

- Dedicated systems have all required components packaged into a single piece of equipment, usually a console with a high quality remote controlled video camera. These cameras can be controlled at a distance to pan left and right, tilt up and down, and zoom. They became known as PTZ cameras. The console contains all electrical interfaces, the control computer, and the software or hardware-based codec. Omnidirectional microphones are connected to the console, as well as a TV monitor with loudspeakers and/or a video projector. There are several types of dedicated videoconferencing devices:

- Large group videoconferencing are built-in, large, expensive devices used for large rooms such as conference rooms and auditoriums.

- Small group videoconferencing are either non-portable or portable, smaller, less expensive devices used for small meeting rooms.

- Individual videoconferencing are usually portable devices, meant for single users, and have fixed cameras, microphones, and loudspeakers integrated into the console.

- Desktop systems are add-ons (hardware boards or software codec) to normal PCs and laptops, transforming them into videoconferencing devices. A range of different cameras and microphones can be used with the codec, which contains the necessary codec and transmission interfaces.

- WebRTC platforms use a web browser instead of dedicated native application software. Solutions such as Adobe Connect and Cisco WebEx can be accessed using a URL sent by the meeting organizer, and various degrees of security can be attached to the virtual room. Often the user must download and install a browser extension to enable access to the local camera and microphone and establish a connection to the meeting. But WebRTC does not require any special software, instead a WebRTC-compliant internet browser itself provides the facilities for 1-to-1 and 1-to-many videoconferencing calls. Several enhancements to WebRTC are provided by independent vendors.

Videoconferencing modes

[edit]Videoconferencing systems use several methods to determine which video feed or feeds to display.[37]: 11–16

Continuous Presence simply displays all participants at the same time, usually with the exception that the viewer either does not see their own feed, or sees their own feed in miniature.

Voice-Activated Switch selectively chooses a feed to display at each endpoint, with the goal of showing the person who is currently speaking. This is done by choosing the feed (other than the viewer) which has the loudest audio input (perhaps with some filtering to avoid switching for very short-lived volume spikes). Often, if no remote parties are currently speaking, the feed with the last speaker remains on the screen.

Echo cancellation

[edit]Acoustic echo cancellation (AEC) is a processing algorithm that uses the knowledge of audio output to monitor audio input and filter from it noises that echo back after some time delay. If unattended, these echoes can be re-amplified several times, leading to problems including:

- The remote party hearing their own voice coming back at them (usually significantly delayed)

- Strong reverberation, which makes the voice channel useless

- Howling created by feedback

Echo cancellation is a processor-intensive task that usually works over a narrow range of sound delays.

Bandwidth requirements

[edit]

Videophones have historically employed a variety of transmission and reception bandwidths, which can be understood as data transmission speeds. The lower the transmission/reception bandwidth, the lower the data transfer rate, resulting in a progressively limited and poorer image quality (i.e. lower resolution and/or frame rate). Data transfer rates and live video image quality are related but are also subject to other factors such as data compression techniques. Some early videophones employed very low data transmission rates with a resulting poor video quality.

Broadband bandwidth is often called high-speed, because it usually has a high rate of data transmission. In general, any connection of 256 kbit/s (0.256 Mbit/s) or greater is more concisely considered broadband Internet. The International Telecommunication Union Telecommunication Standardization Sector (ITU-T) recommendation I.113 has defined broadband as a transmission capacity at 1.5 to 2 Mbit/s. The Federal Communications Commission (United States) definition of broadband is 25 Mbit/s.[38]

Currently, adequate video for some purposes becomes possible at data rates lower than the ITU-T broadband definition, with rates of 768 kbit/s and 384 kbit/s used for some videoconferencing applications, and rates as low as 100 kbit/s used for videophones using H.264/MPEG-4 AVC compression protocols. The newer MPEG-4 video and audio compression format can deliver high-quality video at 2 Mbit/s, which is at the low end of cable modem and ADSL broadband performance.[citation needed]

Standards

[edit]

The International Telecommunication Union (ITU) has three umbrellas of standards for videoconferencing:

- ITU H.320 is known as the standard for public switched telephone networks (PSTN) or videoconferencing over integrated services digital networks. While still prevalent in Europe, ISDN was never widely adopted in the United States and Canada.[citation needed]

- ITU H.264 Scalable Video Coding (SVC) is a compression standard that enables videoconferencing systems to achieve highly error resilient Internet Protocol (IP) video transmissions over the public Internet without quality-of-service enhanced lines.[39] This standard has enabled wide scale deployment of high definition desktop videoconferencing and made possible new architectures,[40] which reduces latency between the transmitting sources and receivers, resulting in more fluid communication without pauses. In addition, an attractive factor for IP videoconferencing is that it is easier to set up for use along with web conferencing and data collaboration. These combined technologies enable users to have a richer multimedia environment for live meetings, collaboration and presentations.

- ITU-T V.80: videoconferencing is generally compatibilized with H.324 standard point-to-point videotelephony over regular (POTS) phone lines.

The Unified Communications Interoperability Forum (UCIF), a non-profit alliance between communications vendors, launched in May 2010. The organization's vision is to maximize the interoperability of UC based on existing standards. Founding members of UCIF include HP, Microsoft, Polycom, Logitech/Lifesize, and Juniper Networks.[41][42]

Call setup

[edit]Videoconferencing in the late 20th century was limited to the H.323 protocol (notably Cisco's SCCP implementation was an exception), but newer videophones often use SIP, which is often easier to set up in home networking environments.[43] It is a text-based protocol, incorporating many elements of the Hypertext Transfer Protocol (HTTP) and the Simple Mail Transfer Protocol (SMTP).[44] H.323 is still used, but more commonly for business videoconferencing, while SIP is more commonly used in personal consumer videophones. A number of call-setup methods based on instant messaging protocols such as Skype also now provide video.

Another protocol used by videophones is H.324, which mixes call setup and video compression. Videophones that work on regular phone lines typically use H.324, but the bandwidth is limited by the modem to around 33 kbit/s, limiting the video quality and frame rate. A slightly modified version of H.324 called 3G-324M defined by 3GPP is also used by some cellphones that allow video calls, typically for use only in UMTS networks.[45][46]

There is also H.320 standard, which specified technical requirements for narrow-band visual telephone systems and terminal equipment, typically for videoconferencing and videophone services. It applied mostly to dedicated circuit-based switched network (point-to-point) connections of moderate or high bandwidth, such as through the medium-bandwidth ISDN digital phone protocol or a fractionated high bandwidth T1 lines. Modern products based on H.320 standard usually support also H.323 standard.[47]

The IAX2 protocol also supports videophone calls natively, using the protocol's own capabilities to transport alternate media streams. A few hobbyists obtained the Nortel 1535 Color SIP Videophone cheaply in 2010 as surplus after Nortel's bankruptcy and deployed the sets on the Asterisk (PBX) platform. While additional software is required to patch together multiple video feeds for conference calls or convert between dissimilar video standards, SIP calls between two identical handsets within the same PBX were relatively straightforward.[48]

Conferencing layers

[edit]The components within a videoconferencing system can be divided up into several different layers: User Interface, Conference Control, Control or Signaling Plane, and Media Plane.

Videoconferencing User Interfaces (VUI) can be either graphical or voice-responsive. Many in the industry have encountered both types of interface, and normally a graphical interface is encountered on a computer. User interfaces for conferencing have a number of different uses; they can be used for scheduling, setup, and making a video call. Through the user interface, the administrator is able to control the other three layers of the system.

Conference Control performs resource allocation, management, and routing. This layer along with the User Interface creates meetings (scheduled or unscheduled) or adds and removes participants from a conference.

Control (Signaling) Plane contains the stacks that signal different endpoints to create a call and/or a conference. Signals can be, but are not limited to, H.323 and Session Initiation Protocol (SIP) Protocols. These signals control incoming and outgoing connections as well as session parameters.

The Media Plane controls the audio and video mixing and streaming. This layer manages Real-Time Transport Protocols, User Datagram Packets (UDP) and Real-Time Transport Control Protocol (RTCP). The RTP and UDP normally carry information such the payload type which is the type of codec, frame rate, video size, and many others. RTCP on the other hand acts as a quality control Protocol for detecting errors during streaming.[37]

Multipoint control

[edit]Simultaneous videoconferencing among three or more remote points is possible in a hardware-based system by means of a Multipoint Control Unit (MCU). This is a bridge that interconnects calls from several sources (in a similar way to the audio conference call). All parties call the MCU, or the MCU can also call the parties which are going to participate, in sequence. There are MCU bridges for IP and ISDN-based videoconferencing. There are MCUs which are pure software and others that are a combination of hardware and software. An MCU is characterized according to the number of simultaneous calls it can handle, its ability to conduct transposing of data rates and protocols, and features such as Continuous Presence, in which multiple parties can be seen on-screen at once. MCUs can be stand-alone hardware devices, or they can be embedded into dedicated videoconferencing units.

The MCU consists of two logical components:

- A single multipoint controller (MC), and

- Multipoint Processors (MP), sometimes referred to as the mixer.

The MC controls the conferencing while it is active on the signaling plane, which is simply where the system manages conferencing creation, endpoint signaling and in-conferencing controls. This component negotiates parameters with every endpoint in the network and controls conferencing resources. While the MC controls resources and signaling negotiations, the MP operates on the media plane and receives media from each endpoint. The MP generates output streams from each endpoint and redirects the information to other endpoints in the conference.

Some systems are capable of multipoint conferencing with no MCU, stand-alone, embedded or otherwise. These use a standards-based H.323 technique known as decentralized multipoint, where each station in a multipoint call exchanges video and audio directly with the other stations with no central manager or other bottleneck. The advantages of this technique are that the video and audio will generally be of higher quality because they do not have to be relayed through a central point. Also, users can make ad hoc multipoint calls without any concern for the availability or control of an MCU. This added convenience and quality comes at the expense of some increased network bandwidth, because every station must transmit to every other station directly.[37]

Cloud storage

[edit]Cloud-based videoconferencing can be used without the hardware generally required by other videoconferencing systems, and can be designed for use by SMEs,[49] or larger international or multinational corporations like Facebook.[50][51] Cloud-based systems can handle either 2D or 3D video broadcasting.[52] Cloud-based systems can also implement mobile calls, VOIP, and other forms of video calling. They can also come with a video recording function to archive past meetings.[53]

Impact

[edit]This article needs to be updated. (February 2015) |

High speed Internet connectivity has become more widely available and affordable, as has good-quality video capture and display hardware. Consequently, personal videoconferencing systems based on webcams, personal computer systems, software compression, and the Internet have become progressively more affordable by the general public. The availability of freeware (often as part of chat programs) has made software based videoconferencing accessible to many.

The widest deployment of videotelephony now occurs in mobile phones. Nearly all mobile phones supporting UMTS networks can work as videophones using their internal cameras and are able to make video calls wirelessly to other UMTS users anywhere.[citation needed] As of the second quarter of 2007, there are over 131 million UMTS users (and hence potential videophone users), on 134 networks in 59 countries.[citation needed] Mobile phones can also use broadband wireless Internet, whether through the cell phone network or over a local Wi-Fi connection, along with software-based videophone apps to make calls to any video-capable Internet user, whether mobile or fixed.

Deaf, hard-of-hearing, and mute individuals have a particular role in the development of affordable high-quality videotelephony as a means of communicating with each other in sign language. Unlike Video Relay Service, which is intended to support communication between a caller using sign language and another party using spoken language, videoconferencing can be used directly between two deaf signers.

Videophones are increasingly used in the provision of telemedicine to the elderly, disabled, and to those in remote locations, where the ease and convenience of quickly obtaining diagnostic and consultative medical services are readily apparent.[54] In one single instance quoted in 2006: "A nurse-led clinic at Letham has received positive feedback on a trial of a video-link which allowed 60 pensioners to be assessed by medics without traveling to a doctor's office or medical clinic."[54] A further improvement in telemedical services has been the development of new technology incorporated into special videophones to permit remote diagnostic services, such as blood sugar level, blood pressure, and vital signs monitoring. Such units are capable of relaying both regular audio-video plus medical data over either standard (POTS) telephone or newer broadband lines.[55]

Videotelephony has also been deployed in corporate teleconferencing, also available through the use of public access videoconferencing rooms. A higher level of videoconferencing that employs advanced telecommunication technologies and high-resolution displays is called telepresence.

Today the principles, if not the precise mechanisms, of a videophone are employed by many users worldwide in the form of webcam videocalls using personal computers, with inexpensive webcams, microphones, and free video calling Web client programs. Thus an activity that was disappointing as a separate service has found a niche as a minor feature in software products intended for other purposes.

According to Juniper Research, smartphone videophone users will reach 29 million by 2015 globally.[56]

A study conducted by Pew Research in 2010, revealed that 7% of Americans have made a mobile video call.[57]

Government and law

[edit]In the United States, videoconferencing has allowed testimony to be used for an individual who is unable or prefers not to attend the physical legal settings or would be subjected to severe psychological stress in doing so, however, there is a controversy on the use of testimony by foreign or unavailable witnesses via video transmission, regarding the violation of the Confrontation Clause of the Sixth Amendment of the U.S. Constitution.[58]

In a military investigation in North Carolina, Afghan witnesses have testified via videoconferencing.

In Hall County, Georgia, videoconferencing systems are used for initial court appearances. The systems link jails with courtrooms, reducing the expenses and security risks of transporting prisoners to the courtroom.[59]

The U.S. Social Security Administration (SSA), which oversees the world's largest administrative judicial system under its Office of Disability Adjudication and Review (ODAR),[60] has made extensive use of videoconferencing to conduct hearings at remote locations.[61] In Fiscal Year (FY) 2009, the U.S. Social Security Administration (SSA) conducted 86,320 videoconferenced hearings, a 55% increase over FY 2008.[62] In August 2010, the SSA opened its fifth and largest videoconferencing-only National Hearing Center (NHC), in St. Louis, Missouri. This continues the SSA's effort to use video hearings as a means to clear its substantial hearing backlog. Since 2007, the SSA has also established NHCs in Albuquerque, New Mexico, Baltimore, Maryland, Falls Church, Virginia, and Chicago.[60]

Education

[edit]

Videoconferencing provides students with the chance to learn by participating in two-way communication forums. Because it is live, videotelephony allows teachers to access remote or otherwise isolated learners. Students from diverse communities and backgrounds can come together to learn about one another through practices known as telecollaboration[63][64] (in foreign language education) and virtual exchange, although language barriers will continue to be present. Such students are able to explore, communicate, analyze, and share information and ideas with one another.

Through videoconferencing, students can visit other parts of the world, including museums and other cultural and educational sites. Such virtual field trips can provide enriched learning opportunities to students, especially those who are geographically isolated or economically disadvantaged. Small schools can use these technologies to pool resources and provide courses, such as in foreign languages, which could not otherwise be offered.

Some benefits that videoconferencing can provide to education include:

- faculty members keeping in touch with classes while attending conferences;

- faculty members attending conferences 'virtually'[65][66]

- guest lecturers brought in classes from other institutions;[67]

- researchers collaborating with colleagues at other institutions on a regular basis without loss of time due to travel;

- schools with multiple campuses collaborating and sharing professors;[68]

- schools from two separate nations engaging in cross-cultural exchanges;[69]

- faculty members participating in thesis defenses at other institutions;

- administrators on tight schedules collaborating on budget preparation from different parts of campus;

- faculty committee auditioning scholarship candidates;

- researchers answering questions about grant proposals from agencies or review committees;

- alternative enrollment structures to purely in-person attendance;

- student interviews with employers in other cities, and

- teleseminars.

Medicine and health

[edit]Videoconferencing is a highly useful technology for real time telemedicine and telenursing applications, such as diagnosis, consulting, prevention, treatment, and transmission of medical images.[70] With videoconferencing, patients may contact nurses and physicians in emergency or routine situations; physicians and other paramedical professionals can discuss cases across large distances. Rural areas can use this technology for diagnostic purposes, thus saving lives and making more efficient use of health care money. For example, a rural medical center in Ohio used videoconferencing to successfully cut the number of transfers of sick infants to a hospital 70 miles (110 km) away. This had previously cost nearly $10,000 per transfer.[71]

Special peripherals such as microscopes fitted with digital cameras, videoendoscopes, medical ultrasound imaging devices, otoscopes, etc., can be used in conjunction with videoconferencing equipment to transmit data about a patient. Recent developments in mobile collaboration on hand-held mobile devices have also extended video-conferencing capabilities to locations previously unreachable, such as a remote community, long-term care facility, or a patient's home.[72]

Business

[edit]Videoconferencing can enable individuals in distant locations to participate in meetings on short notice, with time and money savings. Technology such as VoIP can be used in conjunction with desktop videoconferencing to enable low-cost face-to-face business meetings without leaving the desk, especially for businesses with widespread offices. The technology is also used for remote work. One research report based on a sampling of 1,800 corporate employees showed that, as of June 2010, 54% of the respondents with access to videoconferencing used it "all of the time" or "frequently".[73][74]

Intel Corporation have used videoconferencing to reduce both costs and environmental impacts of its business operations.[75]

Videoconferencing is also currently being introduced on online networking websites, in order to help businesses form profitable relationships quickly and efficiently without leaving their place of work. This has been leveraged by banks to connect busy banking professionals with customers in various locations using video banking technology.

Videoconferencing on hand-held mobile devices (mobile collaboration technology) is being used in industries such as manufacturing, energy, healthcare, insurance, government, and public safety. Live, visual interaction removes traditional restrictions of distance and time, often in locations previously unreachable, such as a manufacturing plant floor thousands of miles away.[76]

In the increasingly globalized film industry, videoconferencing has become useful as a method by which creative talent in many different locations can collaborate closely on the complex details of film production. For example, for the 2013 award-winning animated film Frozen, Burbank-based Walt Disney Animation Studios hired the New York City-based husband-and-wife songwriting team of Robert Lopez and Kristen Anderson-Lopez to write the songs, which required two-hour-long transcontinental videoconferences nearly every weekday for about 14 months.[77][78][79][80]

With the development of lower-cost endpoints, the integration of video cameras into personal computers and mobile devices, and software applications such as FaceTime, Skype, Teams, BlueJeans and Zoom, videoconferencing has changed from just a business-to-business offering to include business-to-consumer (and consumer-to-consumer) use.

Although videoconferencing has frequently proven its value, research has shown that some non-managerial employees prefer not to use it due to several factors, including anxiety.[81] Some such anxieties can often be avoided if managers use the technology as part of the normal course of business. Remote workers can also adopt certain behaviors and best practices to stay connected with their co-workers and company.[82][better source needed]

Researchers also find that attendees of business and medical videoconferences must work harder to interpret information delivered during a conference than they would if they attended face-to-face.[83] They recommend that those coordinating videoconferences make adjustments to their conferencing procedures and equipment.

Press

[edit]The concept of press videoconferencing was developed in October 2007 by the PanAfrican Press Association (APPA), a Paris France-based non-governmental organization, to allow African journalists to participate in international press conferences on developmental and good governance issues.

Press videoconferencing permits international press conferences via videoconferencing over the Internet. Journalists can participate on an international press conference from any location, without leaving their offices or countries. They need only be seated by a computer connected to the Internet in order to ask their questions.

In 2004, the International Monetary Fund introduced the Online Media Briefing Center, a password-protected site available only to professional journalists. The site enables the IMF to present press briefings globally and facilitates direct questions to briefers from the press. The site has been copied by other international organizations since its inception. More than 4,000 journalists worldwide are currently registered with the IMF.

Sign language

[edit]

One of the first demonstrations of the ability for telecommunications to help sign language users communicate with each other occurred when AT&T's videophone (trademarked as the Picturephone) was introduced to the public at the 1964 New York World's Fair—two deaf users were able to communicate freely with each other between the fair and another city.[84] Various universities and other organizations, including British Telecom's Martlesham facility, have also conducted extensive research on signing via video telephony.[85][86][87]

The use of sign language via videotelephony was hampered for many years due to the difficulty of its use over slow analog copper phone lines,[86] coupled with the high cost of better quality ISDN (data) phone lines.[85] Those factors largely disappeared with the introduction of more efficient and powerful video codecs and the advent of lower-cost high-speed ISDN data and IP (Internet) services in the 1990s.

21st-century improvements

[edit]Significant improvements in video call quality of service for the deaf occurred in the United States in 2003 when Sorenson Media Inc. (formerly Sorenson Vision Inc.), a video compression software coding company, developed its VP-100 model stand-alone videophone specifically for the deaf community. It was designed to output its video to the user's television in order to lower the cost of acquisition and to offer remote control and a powerful video compression codec for unequaled video quality and ease of use with video relay services. Favorable reviews quickly led to its popular usage at educational facilities for the deaf, and from there to the greater deaf community.[88]

Coupled with similar high-quality videophones introduced by other electronics manufacturers, the availability of high-speed Internet, and sponsored video relay services authorized by the U.S. Federal Communications Commission in 2002, VRS services for the deaf underwent rapid growth in that country.[88]

Using such video equipment in the present day, the deaf, hard-of-hearing, and speech-impaired can communicate between themselves and with hearing individuals using sign language. The United States and several other countries compensate companies to provide video relay services (VRS). Telecommunication equipment can be used to talk to others via a sign language interpreter, who uses a conventional telephone at the same time to communicate with the deaf person's party. Video equipment is also used to do on-site sign language translation via Video Remote Interpreting (VRI). The relatively low cost and widespread availability of 3G mobile phone technology with video calling capabilities have given deaf and speech-impaired users a greater ability to communicate with the same ease as others. Some wireless operators have even started free sign language gateways.

Sign language interpretation services via VRS or by VRI are useful in the present day where one of the parties is deaf, hard-of-hearing, or speech-impaired (mute). In such cases the interpretation flow is normally within the same principal language, such as French Sign Language (LSF) to spoken French, Spanish Sign Language (LSE) to spoken Spanish, British Sign Language (BSL) to spoken English, and American Sign Language (ASL) also to spoken English (since BSL and ASL are completely distinct from each other), German Sign Language (DGS) to spoken German, and so on.

Multilingual sign language interpreters, who can also translate as well across principal languages (such as a multilingual interpreter interpreting a call from a deaf person using ASL to reserve a hotel room at a hotel in the Dominican Republic whose staff speaks Spanish only, therefore the interpreter has to use ASL, spoken Spanish, and spoken English to facilitate the call for the deaf person), are also available, albeit less frequently. Such activities involve considerable mental processing efforts on the part of the translator, since sign languages are distinct natural languages with their own construction, semantics and syntax, different from the aural version of the same principal language.

With video interpreting, sign language interpreters work remotely with live video and audio feeds, so that the interpreter can see the deaf or mute party, and converse with the hearing party, and vice versa. Much like telephone interpreting, video interpreting can be used for situations in which no on-site interpreters are available. However, video interpreting cannot be used for situations in which all parties are speaking via telephone alone. VRS and VRI interpretation requires all parties to have the necessary equipment. Some advanced equipment enables interpreters to control the video camera remotely, in order to zoom in and out or to point the camera toward the party that is signing.

Comparison of Sign Language communication tools

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (May 2017) |

| Tool | Owner | Free? | Pure web based?[a] | Works on desktops? | Mobile support? | Uses email? | Required hardware | Installation | Limitations | Specialities | Technologies | Deaf made? | Licensing |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Facebook Messenger | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No | Any mobile | App must be installed, does not require a Facebook account | ? | No | 100% proprietary | |||

| FaceTime | Apple Inc. | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No | Apple hardware only (Desktop or mobile) | App must be installed, requires an Apple ID account | ? | No | 100% proprietary | ||

| Glide (software) | Glide | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | Any mobiles | App must be installed | ? | No | 100% proprietary | ||

| Google Hangouts | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No | Any Desktop or mobiles | App must be installed, requires a Google account | ? | No | 100% proprietary | |||

| Skype | Microsoft | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No | Any Desktop or mobile | App must be installed, requires a Microsoft account | ? | No | 100% proprietary | ||

| Tikatoy Archived 2019-01-08 at the Wayback Machine | Tikatoy Archived 2019-01-08 at the Wayback Machine | Yes | No | Yes | Android only | Yes | Desktop or Android | Requires a web browser with Adobe Flash | Apple blocks Adobe Flash | C++, JavaScript, Python | Yes | 100% proprietary | |

| videomail.io | Binary Kitchen | Yes | Yes | Yes | Android only | Yes | Desktop or Android, iPhone and Safari only for viewing | Web browser | Recording max 3 minutes, does not work on old browsers | Reusable: can be plugged directly into other websites or as a WordPress plugin ninja-forms-videomail Archived 2018-01-19 at the Wayback Machine | JavaScript | Yes | Mixed. Proprietary server and client is open source[89] |

- ^ Pure web based means, it is using standardized web technologies only such as HTML, JavaScript and CSS.

Descriptive names and terminology

[edit]The name videophone never became as standardized as its earlier counterpart telephone, resulting in a variety of names and terms being used worldwide, and even within the same region or country. Videophones are also known as video phones, videotelephones (or video telephones) and often by an early trademarked name Picturephone, which was the world's first commercial videophone produced in volume. The compound name videophone slowly entered into general use after 1950,[90] although video telephone likely entered the lexicon earlier after video was coined in 1935.[91]

Videophone calls (also: videocalls, video chat)[92] as well as Skype and Skyping in verb form[93] differ from videoconferencing in that they expect to serve individuals, not groups.[2] However that distinction has become increasingly blurred with technology improvements such as increased bandwidth and sophisticated software clients that can allow for multiple parties on a call. In general everyday usage the term videoconferencing is now frequently used instead of videocall for point-to-point calls between two units. Both videophone calls and videoconferencing are also now commonly referred to as a video link.

Webcams are popular, relatively low-cost devices that can provide live video and audio streams via personal computers, and can be used with many software clients for both video calls and videoconferencing.[28]

A videoconference system is generally higher cost than a videophone and deploys greater capabilities. A videoconference (also known as a videoteleconference) allows two or more locations to communicate via live, simultaneous two-way video and audio transmissions. This is often accomplished by the use of a multipoint control unit (a centralized distribution and call management system) or by a similar non-centralized multipoint capability embedded in each videoconferencing unit. Again, technology improvements have circumvented traditional definitions by allowing multiple-party videoconferencing via web-based applications.[94][95]

A telepresence system is a high-end videoconferencing system and service usually employed by enterprise-level corporate offices. Telepresence conference rooms use state-of-the-art room designs, video cameras, displays, sound systems and processors, coupled with high-to-very-high capacity bandwidth transmissions.

Typical uses of the various technologies described above include calling one-to-one or conferencing one-to-many or many-to-many for personal, business, educational, deaf Video Relay Service and tele-medical, diagnostic and rehabilitative purposes.[96] personal videocalls to inmates incarcerated in penitentiaries, and videoconferencing to resolve airline engineering issues at maintenance facilities, are being created or evolving on an ongoing basis.

Other names for videophone that have been used in English are: Viewphone (the British Telecom equivalent to AT&T's Picturephone),[97] and visiophone, a common French translation that has also crept into limited English usage, as well as over twenty less common names and expressions. Latin-based translations of videophone in other languages include vidéophone (French), Bildtelefon (German), videotelefono (Italian), both videófono and videoteléfono (Spanish), both beeldtelefoon and videofoon (Dutch), and videofonía (Catalan).

A telepresence robot (also telerobotics) is a robotically controlled and motorized videoconferencing display to help give a better sense of remote physical presence for communication and collaboration in an office, home, school, etc. when one cannot be there in person. The robotic avatar device can move about and look around at the command of the remote person it represents.[98]

Popular culture

[edit]

In science fiction literature, names commonly associated with videophones include telephonoscope, telephote, viewphone, vidphone, vidfone, and visiphone. The first example was probably the cartoon "Edison's Telephonoscope" by George du Maurier in Punch 1878.[99] In «In the year 2889», published 1889, the French author Jules Verne predicts that «The transmission of speech is an old story; the transmission of images by means of sensitive mirrors connected by wires is a thing but of yesterday.»[100] In many science fiction movies and TV programs that are set in the future, videophones were used as a primary method of communication. One of the first movies where a videophone was used was Fritz Lang's Metropolis (1927).[101]

Other notable examples of videophones in popular culture include an iconic scene from the 1968 film 2001: A Space Odyssey set on Space Station V. The movie was released shortly before AT&T began its efforts to commercialize its Picturephone Mod II service in several cities and depicts a video call to Earth using an advanced AT&T videophone—which it predicts will cost $1.70 for a two-minute call in 2001 (a fraction of the company's real rates on Earth in 1968). Film director Stanley Kubrick strove for scientific accuracy, relying on interviews with scientists and engineers at Bell Labs in the United States. Dr. Larry Rabiner of Bell Labs, discussing videophone research in the documentary 2001: The Making of a Myth, stated that in the mid-to late-1960s videophones "... captured the imagination of the public and ... of Mr. Kubrick and the people who reported to him". In one 2001 movie scene a central character, Dr. Heywood Floyd, calls home to contact his family, a social feature noted in the Making of a Myth. Floyd talks with and views his daughter from a space station in orbit above the Earth, discussing what type of present he should bring home for her.[102][unreliable source][103][104]

Other earlier examples of videophones in popular culture included a videophone that was featured in the Warner Bros. cartoon, Plane Daffy, in which the female spy Hatta Mari used a videophone to communicate with Adolf Hitler (1944), as well as a device with the same functionality has been used by the comic strip character Dick Tracy, who often used his "2-way wrist TV" to communicate with police headquarters.[105] (1964–1977).

By the early 2010s videotelephony and videophones had become commonplace and unremarkable in various forms of media, in part due to their real and ubiquitous presence in common electronic devices and laptop computers. Additionally, TV programming increasingly used videophones to interview subjects of interest and to present live coverage by news correspondents, via the Internet or by satellite links. In the mass market media, the popular U.S. TV talk show hostess Oprah Winfrey incorporated videotelephony into her TV program on a regular basis from May 21, 2009, with an initial episode called Where the Skype Are You?, as part of a marketing agreement with the Internet telecommunication company Skype.[106][107]

See also

[edit]- 3GP and 3G2

- Comparison of web conferencing software

- List of video telecommunication services and product brands

- Media phone

- Mobile VoIP

- Project DIANE—a large U.S. business and social services videoconferencing network

- Teletraining

- U.S.–Soviet Space Bridge

- Visual communication

Notes

[edit]- ^ "Videotelephony". McGraw-Hill Concise Encyclopedia of Science and Technology (5 ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill. 2004.

- ^ a b Mulbach et al, 1995. pg. 291.

- ^ "German Postoffice To Use Television–Telephone For Its Communication System", (Associated Press) The Evening Independent, St. Petersburg, Fl, September 1, 1934

- ^ Peters, C. Brooks, "Talks On 'See-Phone': Television Applied to German Telephones Enables Speakers to See Each Other ...", The New York Times, September 18, 1938

- ^ Robert Stults, Media Space, Xerox PARC, Palo Alto, CA, 1986.

- ^ Harrison, Steve. Media Space: 20+ Years of Mediated Life Archived 2016-05-05 at the Wayback Machine, Springer, 2009, ISBN 1-84882-482-3, ISBN 978-1-84882-482-9.

- ^ a b "Mr. Tobin has been awarded 15 patents in the past 40 years". WilliamJTobin.com. Archived from the original on 2011-05-30. Retrieved 2011-05-18.

- ^ "Entrepreneur of the Year Reveals Secrets to His Success". RTIR (Radio TV Interview Report). April 1, 2011. Archived from the original on 2011-07-24. Retrieved 2011-05-18.

- ^ Huang, Hsiang-Cheh; Fang, Wai-Chi (2007). Intelligent Multimedia Data Hiding: New Directions. Springer. p. 41. ISBN 9783540711698.

- ^ Kyocera visual phone VP-210, Japan, 1999, Science & Society Picture Library, retrieved August 9, 2013.

- ^ a b First mobile videophone introduced, CNN.com website, May 18, 1999.

- ^ Yegulalp, Serdar. Camera phones: A look back and forward Archived 2014-07-04 at the Wayback Machine, Computerworld, May 11, 2012.

- ^ George Ou. "High definition videoconferencing is here". ZDNet. Archived from the original on 2010-05-13.

- ^ Polycom High-Definition (HD) Video Conferencing Archived 2016-04-16 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ VCLink for Mobile Devices—AVer Video Conferencing Archived 2017-03-13 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Callaham, John. Man makes the highest Skype video call ever on top of Mount Everest Archived 2017-05-19 at the Wayback Machine, Neowin.net website, June 25, 2013; which in turn cites:

- Larson, Stephanie. First Skype Call Atop Mt. Everest Raises Thousands for Charity Archived 2016-03-28 at the Wayback Machine, Skype blog, June 24, 2013.

- ^ Beauford, Moshe (March 5, 2020). "With COVID-19 Spreading, Video Conferencing is Booming". UC Today. Retrieved May 21, 2020.

- ^ "StarLeaf | StarLeaf Reveals Scale of Uptake in Video Conferencing Services During Coronavirus Pandemic". RealWire. 2020-05-01. Retrieved 2020-07-24.

- ^ Jiang, Manyu (22 April 2020). "The reason Zoom calls drain your energy". BBC. Retrieved 30 October 2020.

- ^ Rivkin, Wladislaw; Moser, Karin S.; Diestel, Stefan; Alshaikh, Isaac (2024-04-01). "Getting into flow during virtual meetings: How virtual meetings can benefit employee functioning in the work- and home domain". Journal of Vocational Behavior. 150: 103984. doi:10.1016/j.jvb.2024.103984. ISSN 0001-8791.

- ^ Bennett, Andrew A.; Campion, Emily D.; Keeler, Kathleen R.; Keener, Sheila K. (2021-03-01). "Videoconference fatigue? Exploring changes in fatigue after videoconference meetings during COVID-19". Journal of Applied Psychology. 106 (3): 330–344. doi:10.1037/apl0000906. ISSN 1939-1854.

- ^ Nesher Shoshan, Hadar; Wehrt, Wilken (2021-11-01). "Understanding "Zoom fatigue": A mixed-method approach". Applied Psychology. 71 (3): 827–852. doi:10.1111/apps.12360. ISSN 0269-994X.

- ^ Shockley, Kristen M.; Gabriel, Allison S.; Robertson, Daron; Rosen, Christopher C.; Chawla, Nitya; Ganster, Mahira L.; Ezerins, Maira E. (2021-08-01). "The fatiguing effects of camera use in virtual meetings: A within-person field experiment". Journal of Applied Psychology. 106 (8): 1137–1155. doi:10.1037/apl0000948. ISSN 1939-1854.

- ^ Rivkin, Wladislaw; Moser, Karin S.; Diestel, Stefan; Alshaikh, Isaac (2024-04-01). "Getting into flow during virtual meetings: How virtual meetings can benefit employee functioning in the work- and home domain". Journal of Vocational Behavior. 150: 103984. doi:10.1016/j.jvb.2024.103984. ISSN 0001-8791.

- ^ Kuhn, Kristine M. (2022-03-01). "The constant mirror: Self-view and attitudes to virtual meetings". Computers in Human Behavior. 128: 107110. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2021.107110. ISSN 0747-5632.

- ^ Rivkin, Wladislaw; Moser, Karin S.; Diestel, Stefan; Alshaikh, Isaac (2024-04-01). "Getting into flow during virtual meetings: How virtual meetings can benefit employee functioning in the work- and home domain". Journal of Vocational Behavior. 150: 103984. doi:10.1016/j.jvb.2024.103984. ISSN 0001-8791.

- ^ "Facebook announces new Portal video-calling devices, Portal for Business service". CNBC. 21 September 2021. Retrieved 21 September 2021.

- ^ a b Solomon Negash, Michael E. Whitman. Editors: Solomon Negash, Michael E. Whitman, Amy B. Woszczynski, Ken Hoganson, Herbert Mattord. Handbook of Distance Learning for Real-Time and Asynchronous Information Technology Education Archived 2016-05-08 at the Wayback Machine, Idea Group Inc (IGI), 2008, p. 17, ISBN 1-59904-964-3, ISBN 978-1-59904-964-9. Note costing: "... students had the option to install a webcam on their end (a basic webcam costs about $40.00) to view the class in session."

- ^ Perlroth, Nicole. Cameras May Open Up the Board Room to Hackers Archived 2017-08-27 at the Wayback Machine, The New York Times online, January 22, 2012. A version of this article appeared in print on January 23, 2012, on page B1 of the New York edition with the headline: "Conferences Via the Net Called Risky".

- ^ Gates, Bill (2001-09-04). "Michael J. Miller and Bill Gates: Uncut". PC Magazine (Interview). Interviewed by Michael J. Miller. Archived from the original on 2001-11-06.

- ^ Van Meggelen, Jim. The Problem With Video Conferencing Archived January 4, 2006, at the Wayback Machine, 2005.

- ^ Vertegaal, "Explaining Effects of Eye Gaze on Mediated Group Conversations: Amount or Synchronization?" ACM Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work, 2002.

- ^ Computer vision approaches to achieving eye contact appeared in the 1990s, such as Teleconferencing Eye Contact Using a Virtual Camera, ACM CHI 1993. More recently gaze correction systems using only a single camera have been shown, such as. Microsoft's GazeMaster Archived June 22, 2006, at the Wayback Machine system.

- ^ Google Patent

- ^ Chapanis, A; Ochsman, R; Parrish, R (1977). "Studies in interactive communication II: The effects of four communication modes on the linguistic performance of teams during cooperative problem solving". Human Factors. 19 (2): 101–126. doi:10.1177/001872087701900201. S2CID 60494569.

- ^ Percy, Alan. Understanding Latency Archived 2013-05-14 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b c Firestone, Scott (2007). Voice and video conferencing fundamentals. Indianapolis, Ind.: Cisco Press. p. 10. ISBN 978-1-58705-268-2.

- ^ "F.C.C. Sharply Revises Definition of Broadband". 29 January 2015. Archived from the original on 2015-09-06. Retrieved 2016-03-23.

- ^ SVC vs. H.264/AVC Error Resilience Archived August 10, 2009, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ SVC White Papers Archived January 4, 2010, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Unified Communications Interoperability Forum

- ^ Collaboration Vendors Join for Interoperability[permanent dead link]

- ^ RFC 4168, The Stream Control Transmission Protocol (SCTP) as a Transport for the Session Initiation Protocol (SIP), IETF, The Internet Society (2005)

- ^ Johnston, Alan B. (2004). SIP: Understanding the Session Initiation Protocol, Second Edition. Artech House. ISBN 978-1-58053-168-9.

- ^ IMTC. IMTC Press Coverage Archived 2017-03-31 at the Wayback Machine, International Multimedia Telecommunications Consortium (IMTC), April 1, 2001 to November 16, 2004.

- ^ Orr, Eli. News & Analysis: Understanding The 3G-324M Spec Archived 2013-05-11 at the Wayback Machine, EETimes.com website. January 21, 2003.

- ^ Videoconferencing on the High End: H.320 Archived May 16, 2009, at the Wayback Machine Retrieved on 2009-06-18.

- ^ "2010 Bargain of the Year: Nortel 1535 Color SIP Videophone – Nerd Vittles". Archived from the original on 2017-06-08. Retrieved 2015-01-19.

- ^ "PDS and Vidtel Enable Affordable, Cloud-Based, Interoperable Video Conferencing for Southeast Michigan Businesses". Information Technology Newsweekly. December 27, 2011. Archived from the original on June 11, 2014. Retrieved February 19, 2014.

- ^ Ralph Stair and George Reynolds (2013). Principles of Information Systems. Cengage Learning. p. 288. ISBN 978-1285414775. Archived from the original on May 11, 2016. Retrieved February 19, 2014.

- ^ Stacy Collett (January 30, 2014). "Facebook CIO Supports Video Calls to Preserve Employee Culture". CIO Magazine. Archived from the original on February 13, 2014. Retrieved February 19, 2014.

- ^ ""Cloud-Based Interoperability Platform for Video Conferencing" in Patent Application Approval Process". Politics & Government Week. May 23, 2013. Archived from the original on June 11, 2014. Retrieved February 19, 2014.

- ^ Nitin Pradhan (January 23, 2014). "Better Videoconferencing In The Cloud". Information Week. Archived from the original on February 24, 2014. Retrieved February 19, 2014.

- ^ a b Videophone Scheme Could Provide 'Virtual Care' for Elderly Residents Archived 2013-05-11 at the Wayback Machine, Aberdeen Press & Journal (UK), published in Europe Intelligence Wire, 13 November 2006, retrieved 2009-04-14;

- ^ "Motion Media Unveils Two New Healthcare Videophones—CareStation 156s and CareStation 126s", Business Wire, May 3, 2004.

- ^ Smartphone Video Call Users to reach 29 million by 2015 Globally, finds Juniper Research Archived 2014-06-26 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "7% Of All Americans Have Made A Mobile Video Call". theappwhisperer.com. 14 October 2010. Archived from the original on 25 December 2013.

- ^ Tokson, Matthew J. Virtual Confrontation: Is Videoconference Testimony by an Unavailable Witness Constitutional?, University of Chicago Law Review, 2007, Vol. 74, No. 4.

- ^ Case Study: Hall County Archived 2012-07-22 at the Wayback Machine, Lifesize.com website.

- ^ a b U.S. Social Security Administration. New National Hearing Centre Archived 2016-04-16 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ ODAE Pubs: 70-067 Archived February 9, 2011, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ SSA Overview Performance Archived 2017-05-06 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Dooly, Melinda (2017). "Telecollaboration". The Handbook of Technology and Second Language Teaching and Learning. Wiley-Blackwell. pp. 169–183. doi:10.1002/9781118914069.ch12. ISBN 9781118914069.

- ^ Guth, Sarah; Helm, Francesca (2010). Telecollaboration 2.0. doi:10.3726/978-3-0351-0013-6. hdl:11577/2418350. ISBN 9783035100136.

- ^ "Virtually Connecting".

- ^ Caines, Autums (2016-09-06). "Digital Pedagogy Lab".

- ^ LifeSize Case Study Archived 2012-07-22 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ LifeSize Case Study Archived 2012-07-23 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ AVer Case Study Archived 2017-07-18 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Albritton, Jordan; Ortiz, Alexa; Wines, Roberta; Booth, Graham; DiBello, Michael; Brown, Stephen; Gartlehner, Gerald; Crotty, Karen (2022). "Video Teleconferencing for Disease Prevention, Diagnosis, and Treatment: A Rapid Review". Annals of Internal Medicine. 175 (2): 256–266. doi:10.7326/M21-3511. ISSN 0003-4819. PMID 34871056. S2CID 244923066.

- ^ Adena Health System Uses Lifesize High Definition Video to Bring Remote Specialists to Infant Patients Archived 2017-07-07 at the Wayback Machine (media release), Lifesize.com website, December 8, 2008.

- ^ Van't Haaff, Corey. Virtually On-sight Archived 2012-03-24 at the Wayback Machine, Just for Canadian Doctors, March–April 2009, p. 22.

- ^ By Alison Diane, InformationWeek. "Executives Demand Communications Arsenal Archived 2010-11-20 at the Wayback Machine." September 30, 2010. Retrieved October 5, 2010.

- ^ How We Work: Communication Trends of Business Professionals Archived 2010-12-23 at the Wayback Machine, Plantronics Inc., 2010. Retrieved October 13, 2010.

- ^ E. Curry, B. Guyon, C. Sheridan, and B. Donnellan, "Developing a Sustainable IT Capability: Lessons From Intel's Journey", MIS Quarterly Executive, vol. 11, no. 2, pp. 61–74, 2012.

- ^ "

Mobile video system visually connects global plant floor engineers". Archived from the original on August 20, 2011. Retrieved May 23, 2011., Mobile video system visually connects global plant floor engineers, Control Engineering, May 28, 2009 - ^ Hogg, Trevor (26 March 2014). "Snowed Under: Chris Buck talks about Frozen". Flickering Myth. Archived from the original on 26 March 2014. Retrieved 26 March 2014.

- ^ Truax, Jackson (November 27, 2013). "Frozen composers Robert Lopez and Kristen Anderson-Lopez". Awards Daily. Archived from the original on January 4, 2014. Retrieved January 4, 2014.

- ^ Ziemba, Christine (March 3, 2014). "Disney's Frozen Wins Academy Award for Animated Feature". 24700: News from California Institute of the Arts. California Institute of the Arts. Archived from the original on March 11, 2014. Retrieved March 23, 2014.

- ^ Kit, Zorianna (November 26, 2013). "Awards Spotlight: 'Frozen' Director Chris Buck on Crafting Well-Rounded Female Characters". Studio System News. Archived from the original on March 24, 2014. Retrieved March 23, 2014.

- ^ Wolfe, Mark. "Broadband videoconferencing as knowledge management tool", Journal of Knowledge Management 11, no. 2 (2007)

- ^ Freeman, Michael, "How to stay connected while working remotely", Highfive Blog, December 3, 2014.

- ^ [1][permanent dead link] Ferran, Carlos and Watts, Stephanie. "Videoconferencing in the field: A heuristic processing model", Management Science 54, no. 9 (2008)

- ^ Bell Laboratories RECORD (1969) A collection of several articles on the AT&T Picturephone Archived 2012-06-23 at the Wayback Machine (then about to be released) Bell Laboratories, pp. 134–153 & 160–187, Volume 47, No. 5, May/June 1969.

- ^ a b New Scientist. Telephones Come To Terms With Sign Language Archived 2016-05-06 at the Wayback Machine, New Scientist, 19 August 1989, Vol.123, Iss.No.1678, pp.31.

- ^ a b Sperling, George (1980). "Bandwidth Requirements for Video Transmission of American Sign Language and Finger Spelling" (PDF). Science. 210 (4471): 797–799. Bibcode:1980Sci...210..797S. doi:10.1126/science.7433998. PMID 7433998.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Whybray, M.W. Moving Picture Transmission at Low Bitrates for Sign Language Communication Archived 2017-07-02 at the Wayback Machine, Martlesham, England: British Telecom Laboratories, 1995.

- ^ a b Fitzgerald, Thomas J. For the Deaf, Communication Without the Wait[permanent dead link], The New York Times, December 18, 2003.

- ^ "videomail-client source code on GitHub". GitHub. 23 July 2022.

- ^ Videophone definition Archived 2017-02-04 at the Wayback Machine, Merriam-Webster Online. Retrieved April 13, 2009

- ^ Video definition Archived 2017-02-03 at the Wayback Machine, Online Etymology Dictionary

- ^ PC Magazine. Definition: Video Calling Archived 2012-10-12 at the Wayback Machine, PC Magazine website. Retrieved August 19, 2010