Autoinjector

An autoinjector (or auto-injector) is a medical device for injection of a premeasured dose of a particular drug. Most autoinjectors are one-use, disposable, spring-loaded syringes (prefilled syringes). By design, autoinjectors are easy to use and are intended for self-administration by patients, administration by untrained personnel, or easy use by healthcare professionals; they can also overcome the hesitation associated with self-administration using a needle.[1] The site of injection depends on the drug, but it typically is administered into the thigh or the buttocks.[citation needed]

Autoinjectors are sharps waste.[citation needed]

History

[edit]Automatic syringes are known since the 1910s,[2] and many spring-loaded devices with needle protectors were patented in the first half of the 20th century,[3] but it was not until 1970s when they became economically feasible to mass-produce (simple syrettes were used instead before). In 2023 an open source autoinjector was developed that could be digitally replicated with a low cost desktop 3D printer.[4] It was tested against the then current standard (ISO 11608–1:2022)[5] for needle-based injection systems and found to cost less than mass manufactured systems.[4]

Design

[edit]

Designs exist for both intramuscular and subcutaneous injection. Disposable autoinjectors commonly use a pre-loaded spring as a power source. This spring and the associated mechanical components form a one-shot linear actuator.[citation needed] When triggered the actuator drives a three-step sequence:[citation needed]

- accelerate the syringe forward, puncturing the injection site

- actuate the piston of the syringe, injecting the drug

- deploy a shield to cover the needle

Some injectors are triggered by simply pushing the nose ring against the injection site. In these designs, the protective cap is the primary safety. Other designs use a safety mechanism similar to nail guns: The injection is triggered by pushing the nose ring against the injection site and simultaneously, while applying pressure, pushing a trigger button at the rear end of the device.[citation needed]

Since spent autoinjectors contain a hypodermic needle, they pose a potential biohazard to waste management workers. Hence the protective cap is designed not only to protect the drug and keep the needle sterile but also to provide adequate sharps waste confinement after disposal.[citation needed]

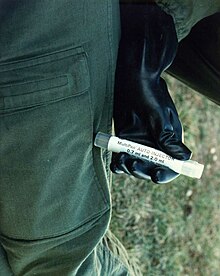

Injectors intended for application through layers of clothing may feature an adjustable injection depth. Other typical features include: A drug inspection window, a color-coded spent indicator, and an audible click after the injection has finished.[citation needed]

Uses

[edit]

- Epinephrine autoinjectors are often prescribed to people who are at risk for anaphylaxis. Brand names include Anapen, EpiPen, Emerade, and Auvi-Q.[citation needed]

- Rebiject, Rebiject II and Rebidose autoinjectors for Rebif, the drug for interferon beta-1a used to treat multiple sclerosis. An autoinjector for the Avonex version of this same medication is also on the market.[citation needed]

- SureClick autoinjector is a combination product for drugs Enbrel or Aranesp to treat rheumatoid arthritis or anemia, respectively.[citation needed]

- Subcutaneous sumatriptan autoinjectors are used to terminate cluster headache attacks.[6]

- Naloxone autoinjectors are being developed and prescribed to recreational opioid users to counteract the deadly effects of opioid overdose.[1]

Military uses include:

- Autoinjectors are often used in the military to protect personnel from chemical warfare agents. In the U.S. military, atropine and 2-PAM-Cl (pralidoxime chloride) are used for first aid ("buddy aid" or "self aid") against nerve agents. An issue item, the Mark I NAAK (Nerve Agent Antidote Kit), provides these drugs in the form of two separate autoinjectors. A newer model, the ATNAA (Antidote Treatment Nerve Agent Auto-Injector), has both drugs in one syringe, allowing for the simplification of administration procedures. In the Gulf War, accidental and unnecessary use of atropine autoinjectors supplied to Israeli civilians proved to be a major medical problem.[7]

- In concert with the Mark I NAAK, diazepam (Valium) autoinjectors, known as CANA, are carried by US service members.[citation needed]

Variants

[edit]Another design has a shape and size of a smartphone which can be put into a pocket. This design also has a retractable needle and automated voice instructions to assist the users on how to correctly use the autoinjector. The "Auvi-Q" epinephrine autoinjector uses this design.[8]

A newer variant of the autoinjector is the gas jet autoinjector, which contains a cylinder of pressurized gas and propels a fine jet of liquid through the skin without using a needle. This has the advantage that patients who fear needles are more accepting of using these devices. The autoinjector can be reloaded, and various doses or different drugs can be used, although the only widespread application to date has been for the administration of insulin in the treatment of diabetes.[9][10]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Dostal P; Taubel J; Lorch U; Aggarwal V; York T (Jul 9, 2023). "The Reliability of Auto-Injectors in Clinical Use: A Systematic Review". Cureus. 15 (7): e41601. doi:10.7759/cureus.41601. PMC 10409493. PMID 37559861.

- ^ GB 143084A Improvements in and relating to self-acting syringes for hypodermic injections

- ^ "Espacenet – search results".

- ^ a b Selvaraj, Anjutha; Kulkarni, Apoorv; Pearce, J. M. (2023-07-14). "Open-source 3-D printable autoinjector: Design, testing, and regulatory limitations". PLOS ONE. 18 (7): e0288696. Bibcode:2023PLoSO..1888696S. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0288696. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 10348544. PMID 37450496.

- ^ "ISO 11608-1:2022". ISO. Retrieved 2023-09-18.

- ^ May, A.; Leone, M.; Áfra, J.; Linde, M.; Sándor, P. S.; Evers, S.; Goadsby, P. J. (2006). "EFNS guidelines on the treatment of cluster headache and other trigeminal-autonomic cephalalgias". European Journal of Neurology. 13 (10): 1066–77. doi:10.1111/j.1468-1331.2006.01566.x. PMID 16987158. S2CID 9432289.

- ^ Baren, Jill M.; Rothrock, Steven G.; Brennan, John; Brown, Lance (2007-10-24). Pediatric Emergency Medicine. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 1069. ISBN 978-1437710304.

- ^ Thomas, Katie (1 February 2013). "Brothers Develop New Device to Halt Allergy Attacks". New York Times. Retrieved 6 March 2017.

- ^ "1". Mendosa.com. 2001-01-16. Retrieved 2010-07-07.

- ^ 2 Archived April 11, 2007, at the Wayback Machine